Basava did not accept the traditional interpretation always and found that the scriptures adore the Supreme Being and not gods and goddesses. He did his best to establish man’s belief in and reverence to the one Supreme Being. He felt pained by the rigidity of Hindu life and he upheld the dignity of man as man by denouncing all social divisions and appropriation of rights after it. Basava was truly great in liberating women from the rigidities of social customs and the oppression of hierarchies. He threw open the sacred literature to every one in society and had the spirit of modernism in him to challenge the aristocracy of birth by the aristocracy of character. Basava was the messenger of a new social construction and the fusion of social forces. The vision of one God enabled him to envisage the one Humanity with the freedom of interchange of ideas and interfusion of cultures.

Basava hailed from a place of the Bijapur district which is now in Karnataka. He flourished in the 12th century being styled as Bhakti-Bhandari, a treasure house of devotion, because of his intense devotion to God and his votaries; and he was also a capable administrator – a rare combination of the fugitiveness of a mystic with the precision of a scientist. He was a Prime Minister to a Jain King, Bijjal who ruled from 1156 to 1166 A.D. over Kalyana which is now situated in the Hydrabad State. He met many problems of his time with remarkable success, and the general principles of life and conduct which he enunciated stand unimpeachable for all time, with the necessary modifications which each generation has to make for itself. The life and teachings of Basava have revealed the truth that he was one of the greatest reformers that India has ever produced. He was resolute and independent thinker as also a man of consistent conduct and candid character – a rare instance of powerful will combined with powerful intellect. Basava was also a great literalist who had left an imperishable mark in the history of Kannada literature. Thus Basava was a saint, a statesman, a social and religious reformer, a great literary figure and above all, a precuros of Veershaiva or Lingayat Movement.

Any community, race or nation has had some philosophy of life to work out the problems which confront the society. Philosophy is not merely the basis of life but it is also the criticism of life. To be a philosopher is not merely to have suitable thoughts, but so to love wisdom as to live according to it dictates. The discovery of what is true and the practice of what is good, are the two important objects of philosophy. If the discovery is not accompanied by practice, mild philosophy degenerates into wild speculation. Philosophy may be religious, agnostic or scientific in accordance with the outlook upon life. The hoary past of India was saturated by religious philosophy, as philosophy was wedded to religion. Since philosophy in India was mainly religious, social progress was possible only through a progressive religion. But when religion ceased to be progressive, it called for a drastic change and reform which necessitated the birth of Buddhism. Buddhism fought the evils of the day crept into the society through the degeneration of religion, and sought the way of life through love and non-violence. After the fall of Buddhism, it was Veershaiva or Lingayat movement sponsored by Basava that brought about a social revolution in Indian life, through religion bolstered up by progressive philosophy. Buddha fought the evils of his days on the agnostic front whereas Basava defeated them through monotheism.

Basava was born at a time when Hinduism has lost its fervour and power and was following customs and traditions somewhat blindly. Basava’s advent marks the beginning of a new revival in culture, in social reform and in religious awakening. His spirit was essentially the spirit of a creative genius who could clearly see the needs of his age and supply the formative spirit for new constructions. He was essentially a builder, he came to fulfill and not to destroy. He saw, in the signs of his times, dormant creative power of varied cultures in India. He envisaged the quintessence of each of them and thus was attracted by the fine transcendence of the Upanishads, the puissant immanence of the Agamas, the concept of Good of Love of Vaishnavism and the concept of Ahimsa or non-violence of Jainism. His catholic mind visualized the future India not as the India of Hindus only but as the India of humanity. He was convinced that the peace and prosperity of the land would depend always upon a wide outlook on life and the receptive spirit which could trace the beauties of every faith and conceive a fine synthesis of them based upon intuition. The mutual responsiveness and sympathy which each faith should awaken in man has often failed to work in the history of the world, when the fine inspiration which is its motive power is lost. Basava was the Messiah of a new age carrying with him the vision of a humanity embraced in ties of spiritual fellowship.

When Hindu society was really being suffocated by the pressure of caste-ism and idolatry from without and by a narrowness nurtured in ignorance from within, Basava appeared and delivered his message of freedom, toleration, democracy and monotheism. His message had a special importance for the land of his birth. The genius of Hinduism lies in supplying a dynamic synthesis of the new forces with the old ones. Of course Hinduism is conservative but its conservative tendency has a wonderful adaptability and integrating power. Conservatism keeps up the spirit of continuity, but does not oppose the adaptability which the life of a nation requires. Conservatism maintains the values that are really essential, adaptability brings in changes that are positively beneficial. Such is the spirit of Hinduism. This spirit becomes once again manifested in the life of Basava.

Basava had a receptive mind, but he was endowed with a critical faculty of a high order. His mind was not prepared to accept the traditional faith prevalent in those days in India. His make-up was fundamentally rational, combined with a very devotional heart and high strung will-power. Basava was not satisfied with the prevalent theology, metaphysics and sociology. He felt that Hindu society was in state of degradation, moral weakness originating from superfluous ceremonials, meaningless rituals an false religious ideas. Love of knowledge was non-existent, study of arts and sciences was neglected. The higher castes oppressed the lower, the strong ill-treated the weak. His receptive mind saw the disease and was anxious for the cure. But Basava was not ready to make the least compromise with caste system and idolatry as did the other teachers of Hindism. In his interpretation of scriptures he took new line and direction. He read life synthetically and saw the economy of all the forces in life. He was never for the elimination of any one of them. Kriya, Japa, Bhakti, Jnana, and Dhyana all have found their proper position and function in the scheme of his Shat-Sthala. Basava was an idealist in philosophy but a realist in his outlook upon life as manifested in the social environment. Though a social democrat he was for a vigorous and manly expression of Hinduism. He was at times pained at the weakness and timidity exhibited in Hinduism. Himself essentially active, he used to impress activity in all concerns of life. The Veershaiva Samaja imbibing from him this vital side, represents today an advanced section of Hinduism, with eager determination to make Hinduism a force in the land of its birth.

Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh released coins commemorating Basava.

Basava was not merely an intellectual moralist but a great spiritual genius. His being was responsive to the fine living currents of the spiritual faiths. He could see the inherent beauties of their teaching and longed to build up a synthesis of the fine powerful elements of all faiths. He culled the fine flowers of spiritual knowledge and intuition from among the foliage of faith and composed them into a bouquet which could be enjoyed by all alike. This was possible for him, not because he was a successful practice man, but because he had in him the finer spiritual receptivity which could respond to all the beauties of life. The Anubhava Mantapa or the spirito-religious academy founded by him was a standing witness to this fact. Basava’s interest in religion was not merely academical, but he lived it. It has been said of him that he went through Agamic and Vedantic disciplines to prepare himself for direct spiritual knowledge. Life and philosophy in Indian teachers have never been separate; indeed their philosophy is the intellectual reflection of their life and this alone explains why Indian teachers of the first rank are always creative and moving. Basava was no exception to this rule. His virility, his vast outlook initiated subtle currents in social life, and he could influence a fine reconstruction of social life.

Basava had varieties of moods like all spiritual men and those moods proceeded from the spiritual centers in the different layers of his being. His being was highly devotional and a devotional being exhibits more varied phases of spirituality than intellectual being. The devotional man generally gives himself uo to God, and the spirit of God when it descends upon man exhibits more phases of being than is otherwise possible. Intellect has not that fine penetration which proceeds from devotion and sympathy. It is not to be wondered at if Basava spoke of varied experiences of the soul, including those of sin and repentance, from consciousness of burning faith to communion with God. Because of his devotional nature, Basava was alive to the sense of union in love. He maintained that Vedic seers realized the fulfillment of their being through objective nature, while the seers of the Upanishadas sought it in the inner subjectivity. If the Vedic seers saw, the Truth in the silent forces of nature, the Upanishadic seers saw it in the silence of the soul. But Basava’s yearning went further. He sought the divine in nature, in man and in the Divine himself. This third phase was to him the culmination in spiritual life, for it would life our vision from the history of the divine expression through time in nature’s working, from the revelation of the shining truths to the finite spirit, to that ever-lasting communion beyond time where spiritual life is presented not in succession but in simultaneity.

Humanity is open but not sufficiently open to the currents of the infinite to see, estimate and realize the beauties and the dignities of the varied expressions of life. Basava’s attempt was to find a rationale that could embrace them all. His being was finely attuned to the Shaivite concept of God, for in it he could find the satisfaction of the soul in its aspiration after the highest wisdom and knowledge. The vision of God as Power or as Love enraptures the soul, but the abiding peace is given in the goodness which is also blessedness. Basava could not break from this spiritual tradition of the Hindus and the delicate intuition which they display when they conceive the idea, of an affinity of the civitas dei peopled by redeemed souls; and surely a finer conception of redemption lies in exhibiting the essential similarity and identity between man and God. Theism in Basava has its final appeal there. Love and power have appeals to the human heart and will; but Blessedness appeals to the depth of the soul, where it crosses the finer life currents and is installed in the majesty of being.

The wide catholicity of his Hindu instinct helped Basava in the speedy reception and assimilation of the vital truths of other faiths. But with all his catholicity of mind he had leanings more towards Shaivism than any other faith. The reason probably is that he was born as a Shiva. He rescued Shaivism from its shackles and purified it of its dross and gave it the name of Veershaivism. Moreover, he found in Shaivism an integral idealism comprehensive enough to embrace both spirit and matter. For Shaivism affiliating the human soul to the Divine and secures for it a fellowship with the Divinity. The soul enjoys the divine majesty and sweetness and, in synthetic vision, the totality of existence is assimilated in the Divine. Life has triune expression in delight, consciousness and existence, and the more the human spirit is affiliated in knowledge to the Divine, as it is in Being, the more it can have the ease of movement and plasticity of life. Thus it is better fitted to realize that the human and the Divine are not separated and that humanity is not totally helpless, for it enjoys the protection of the Divine. The synthetic apprehension and the cosmic intuition can see the play of the Divine in nature, its immanence in the finite spirit and its transcendence in its luminous expression of delight.

Buddha and Basava – The two Luminaries

Basava did not accept the traditional interpretation always and found that the scriptures adore the Supreme Being and not gods and goddesses. He did his best to establish man’s belief in and reverence to the one Supreme Being. He felt pained by the rigidity of Hindu life and he upheld the dignity of man as man by denouncing all social divisions and appropriation of rights after it. Basava was truly great in liberating women from the rigidities of social customs and the oppression of hierarchies. He threw open the sacred literature to every one in society and had the spirit of modernism in him to challenge the aristocracy of birth by the aristocracy of character. Basava was the messenger of a new social construction and the fusion of social forces. The vision of one God enabled him to envisage the one Humanity with the freedom of interchange of ideas and interfusion of cultures.

For Basava gods and angels had no fascination; because he felt that the bondage was self-created and should be broken by self-possession. He maintained the heroic attitude in all concerns of life. True to the realistic instinct, he could feel that power should not be denied to man, for the organization of life forces is impossible without it. And in the regulation of cosmic affairs, will and power are great assets. Buddha, in negating the conception of power and installing in love, forgot that love is a delicate plant that cannot flourish on the soil of earth without the constant protection of power. Power is therefore the needed element which can give practical shape to the forces of love. Where tamas predominates life can hardly make an appeal, for inertia is the shadow of death. Power becomes there a necessity to awaken the finer feelings and to impose better adjustment. �The world is a battle field, fight your way out’, said Basava. In the economy of nature, power has its proper place. The Divinity is not all love, it is also stern will and dominating power. The forces help each other in the complexity of life and its adjustments.

Basava’s policy was to bring in social reformation more by the propagation of liberal and humanistic culture rather than by positive frontal attacks. He was anxious to impart the touch of love and life to everybody, but he was equally anxious to see the spirit of self-reformation coming from within. His church or Anubhava Mantapa invited people of all castes. The fitness was of character and conduct and not of birth. His conception of a monastery was that it must be a center of education and philosophy, so that ultimately it could send forth into the world an army of soldiers of peace, refinement, knowledge and service. Basava actually had sent missionaries to the various parts of India so much so that his liberal church attracted persons of all shades ranging from the prince to the peasant, from the queen to the maid-servant. This missionary zeal did not continue for a long time and in course of time degeneration also set in the order of monks. Hence Veershaiva ceased to be a proselytizing religion.

Dvaita, Visistadvaita and Advaita were to Basava not absolute logical systems, but stages in spiritual growth and experience. In one of his sayings he has boldly criticized the logical quibbles of dvaita and advaita. When logic tries to mould the spiritual experience into systems, it invites conflicts into them. But if life can be released from the thralldom of logic, it exhibits those kinds of experience culminating in the experience of beatific freedom. Basava approached religion and philosophy through an analysis of life and psychic experience, and he welcomed that as the highest which gave the finest idea of freedom. He did not lay much stress upon the metaphysics nor upon the speculative thinking which can only give us systems but not that spirit and insight which enable us to stand face to face with the Supreme. His teachings have, therefore, an appeal to life. He was a prophet of life and philosophy to him had a value in life so far as it helped righteous living and robust realization. Even the isolation of life consequent upon the hard asceticism was to him a bondage. He felt the ill effect of an over-long enforced or self imposed isolation, for he pronounced the verdict that the real test of true culture is not possible in complete social isolation. Isolation may have a value in the beginning, but a too prolonged isolation has the baneful effect of a spiritual slumber. A spiritual fellowship is much better than a spiritual isolation. Hence Basava was the champion of spiritual association and fellowship.

The pangs of death, the afflictions of existence had no sting for Basava. The joys of heaven, the blessings of life had no attraction for him. He stood above them. The deep realization of the self in the deep and august silence made him a hero in the battle-field of life. A great hero is he who has nothing to win but everything to give. With this spirit of love and selflessness based upon the realization of self, the spirit of Basava moved to inspire men and women of his times with freedom in soul and love for all.

Hinduism is a group of religions, the most important members of which are Shaivism, Vaishnaivism and Shaktism, whose authorities are respectively the Shivagamas, the Pancharatra and the Shaktagamas. In spite of their akin ness, they differ widely in their philosophy and rituals. Of these three religions Shaivism has the largest number of followers in India. Veershaivism which is a fine and full blown flower of Shaivisim is mainly confined to Karnataka, though its followers are sparsely scattered all over India. As regards the age of Shaivism, it may be said it is pre-vedic. There seems to be archaeological evidence to show that there was Shiva-worship in the Indus valley five thousand years ago. Sir John Marshall and Dr. Prana Nath have independent of each other, arrived at the conclusion that Shiva-worship had been prevalent there since 3000 B.C. Rama, the hero of Ramayana is said to have established Shivalinga in Rameshwara after the death of Ravanana. It is said that Ravana himself was a devout worshiper of Shivalinga. Reference is made to Shaivism and Shivagamas in the Mahabharat. Puranas and subsequent literature abound in the reference to Shaivism. In Kashmir, Shaivism flourished as a powerful faith and vigorous philosophy till the 12th century. Shankar received an impetus from Kashmir Shaivism to propagate his Advaita philosophy throughout the length and breadth of India. The same Shaivism inspired Basava to launch his Shakti-visistadvaita philosophy in Karnataka. Appar, Sambandar, Sundarar and Manikkavachakar were the exponents of Shaivism in the South. Thus Shaivism has a mighty history and a many sided philosophy from pre-vedic times to the present day.

Shaivism, like Buddhism, Christianity and Islam, is not a creedal religion, deriving its authority and name from a single founder. The truths of Shaivism are discovered by Gnostics who may appear in this world at any time. Prior to Buddhism, it is Shaivism which has proclaimed the validity of the Law of universal causation. Since the law of causation holds good in all the planets of existence, Shaivism states that miracles are only acts that cannot be explained by the knowledge available at present to the scientist. They really obey laws and when these laws are found out by man, miracles will cease to be impressive. Shaivism accepts the evolution of the whole material world and of the souls. The Agamic meaning of the word Maya is that which involves and evolves, and that of Linga, the Shaiva symbol of God, is that which causes involution of the universe, he must be different from Maya. Shiva or God simply directs the unlimited energy existing in the universe. It is in this sense that the ultimate Reality is described in Shavism as the source of all power rather than that He is the possessor of power, the source of all knowledge rather than He s the possessor of all knowledge. In the region of ethics Shaivism regards wrong doing as mere weakness which deserves kind and sympathetic treatment instead of hatred and abhorrence. Wrong acts are those that do not reach the fixed standard. A right act requires reaching a certain standard of knowledge, desire and self-control. The required standard cannot be reached all of a sudden, it has to be reached gradually. Till it is reached the act continues to be wrong. Once the standard is reached, act ceases to be wrong and the right act takes orientation. In psychology, Shaivism has no place for faculties but it divides the mental activities into affection, conation, cognition, volition and intuition. Coming to physics, it regards substances only as aggregates of qualities, and derives all mental and material products alike from the three qualities – inertia, motion and equilibrium – thus making mind and matter at bottom the same.

Shaivism by far a teleological religion. The general argument of teleology has been from the facts of order and adaptation to ends, to the source of order and purposive intelligence. In other words, teleology implies a theory of values; and Shaivism in its treatment of teleology is anticipatory of modern biological statements. That human life and experience is of a rather different and higher quality than that of the amoeba, that there is no reason to suppose the progress in the creation of values to have finished, and that these higher values are not accidental by products but brought into notice. Shaivism posits Good as the aim of life, nay, it holds that life itself is good. Then what is the highest good of life? Is it happiness? Shaivism says; no; happiness usually accompanies the good life, but it does not seem itself to be the highest good. Pleasure accompanies the fulfillment of function, but it is not the motive of action. According to Shaivism, self-realization and social service are the highest good. Self-realization implies a harmoniously developed personality, a condition in which every faculty functions in a perfect way without encroaching upon any other faculty. Social service implies discipline, self-restraint, respect, forlaw, limitation of desire and co-operation – values which condition the existence and welfare of society. In the present day educational system, too much stress has been placed upon self-expression but too little upon character values such as honesty, fidelity, veracity, justice and self-control. When individuals, curbing their selfish interests, learn to live together, when nations, curbing their selfish nationalism learn to live together, then the other values intellectual, aesthetic and recreational may be realized. The lesson of co-operation is clearly the first lesson.

There has been an evolution of man’s moral nature, but his moral nature has not been evolved out of the social instincts of the lower animals, because there is vastly more in moral character than in social instincts. It has been rather a growth in which new qualities and higher values have been slowly realized; it seems more like an epigenesist than like an evolution – a new birth, something achieved, a higher round of the ladder gained. Perhaps the only way that we can hope to understand the evolution of the moral from the non-moral is to believe that there is some force at work, some conative drive, or cosmic interest which is struggling to realize these higher values.

This something Shaivism calls the Will that point to a directed development, the progressive revelation of a Good that transcends the process of evolution.

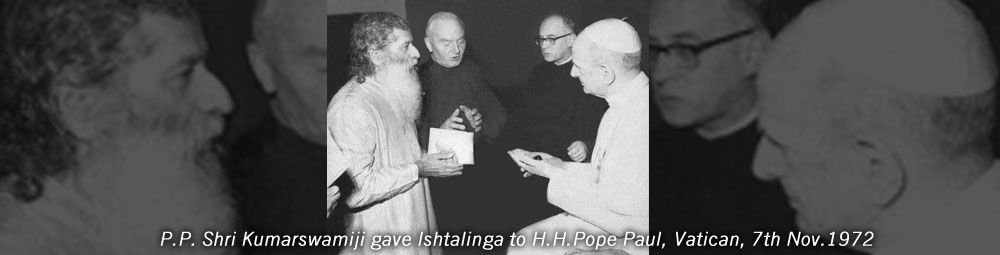

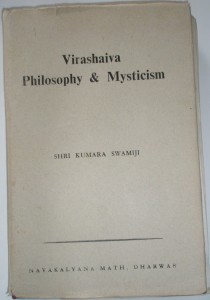

This article – Basava and Hinduism – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Buddha and Basava’.