The idea of the welfare state was first enunciated and practiced by Ashoka. He ruled over a vast empire in a benign spirit. He tells us himself in his edict, “All men are my children, and just as I desire for my children that they may obtain every kind of welfare and happiness both in this and next world, so I desire for all men….. The welfare of the whole world is an esteemed duty with me, and the root of it is exertion and dispatch of business. I can therefore never be satisfied too much with my exertion, or dispatch of my business in the matter of administration… I cause this document of Dharma to be engraved in order that it may endure for a long time and that my sons and grand-sons may similarly exert themselves for the welfare of whole world.”

Basava attempted to formulate the highest good in accordance with the principle of self-realization, bringing the individual and society into their proper relations. “The highest good is” a social order in which the highest potentialities of each indivudal are developed to the maximum, and in which these potentialities are expended in the interests of that order to guarantee its stability and permanence.” In this scheme the organic unity of society, the supremacy of the character values and the principle of self-realization of the individuals in society are recognized. Basava put forward his scheme and tried to work it out in his administration, but unfortunately he could not reap the harvest as he was compelled to leave the capital and take refuge in Kudala Sangama, at the unsavoury turn of events which took place after the marriage of the Brahmin girl with the untouchable boy.

There is a tendency among scholars to institute a comparison between Plato and Manu regarding the structure of the State and its end. When one studies Palto’s Republic side by side with the Hind Dharmshastra, the first thing that strikes him is the similarity between the thoughts of the two, with respect to the problem of the structure of society and the purpose for which the State should exist. It has been observed by the European writers that the social structure recommended by Plato is fundamentally the same as promulgated by the Hindu law-givers, and if practical shape were given to the tenets proclaimed by Plato, a social system of India. In the case of the Greeks the whole thing remained a theoretical proposition, while with the Hindus it became a theoretical proposition, while with the Hindus it became a theoretical which has for better or worse rigorously determined the course of their lives up to the present time. With both, the fundamental conception on which the whole super-structure is raised is based on an analogy. With the Hindu writers the analogue is the limbs of a human being, with Plato, the constituents of the mental nature of man. The difference is not vital because the conclusions derived by both are similar. Both emphasize the inter-dependence of one part on the other; both declare that there are some parts performing higher functions and others comparatively lower ones, and that the baser parts should be controlled by the nobler parts; and both stress the avoidance of encroachment of one on the sphere of the other.

The ideal of the state aimed at by the Greek and the Hindu philosophers remains almost the same. While Plato declares Justice to be the end of the State, the Hindu law-givers make i the end and justification of the State. By justice Plato does not mean the dispensation of what is strictly due to an individual or a body of individuals composing the State, but he means what constitutes his due in a well-organized State. He arrives at the conclusion that justice consists not only in an individual’s performing the work peculiar and congenial to his nature, but also in his abstaining from performing the work properly belonging to an individual of a different type. By Dharma Hindu philosophers mean not merely the performance of duty as ordinarily understood, but like the Greek philosophers their very conception of duty involves the doing of actions by individuals dictated by their very nature. The words Swabhava, individual nature, Swadharma, duties s determined by that nature, and Swakarma, actions flowing there from occur frequently in Hindu religious and secular literature. Therse sum up the Hindu angle of vision with regard to the mutual inter-dependence of society and individual, as also the end to which this harmonious cohesion ought to lead. Adharma consists in the individual’s performing the Dharma belonging to a different type. This confusion of duty of one type with that of another is as emphatically deprecated by the Hindu thinkers as by the Greek philosophers. Thus justice as adumbrated by Plato and Dharma as understood by the Hindu law-givers are not only the same thing in essence, but both have deduced the same practical inferences from them.

This cut and dried organic structure of society, though it pretends to admit the importance of an individual, yet it implies the sense of natural inequality not as a flexible characteristics but as a fundamental attribute. To Plato the society consists of three classes – the legislators representing reason, the warriors, heart and the labourers, appetite. To the Hindu law-givers the society consists of four classes – the legislators, the warriors, traders and labourers. In theory the labourers were admitted as a limb of society, in practice they were denied the rights of a citizen. In Greece they were slaves, in India they were Sudras. In this structure of society the peculiarities of the individuals are ignored and genius often is a peculiarity. Heredity comes to play an important part relegating environment to a low position. Since there is an implied sense of inborn inequality, the division between classes comes to be static. Hence there is no reciprocity of individual good and social well-being. The remarks which Prof. Caird has passed in regard to the social structure of Plato may, with equal force, be applied to the social structure of the Hindus. Caird remarks: “On the one had, sharing, as he (Plato) does, in the Greek view that the higher life is only for the few – for those who are capable of intellectual culture and in proportion as they are capable of it, he is unable to conceive the lower classes, those engaged in agricultural or industrial labours as organic members of the state; he is obliged to regard them as the instruments of a society in whose higher advantages they have no share. And on the other hand, he is so solicitous to exclude all self-seeking and directly to merge private in social good, that he deprives even the forward citizens of personal rights they should become the rival of the state. He thus seems to secure the unity of the state, not by subordinating the personal and private interests of its members but rather by preventing any consciousness of such interest from arising and the result is that he reduces it to a mechanical, instead of raising it to a spiritual or organic unity.”

Basava raised the cry of revolt against this static form of society. He proclaimed that all members of the state are labourers, some may be intellectual labourers, and others may be manual labourers. The strange thing is that he went a step further and declared that every one, whether he may be an intellectual or a manual, must earn his bread in the sweat of his brow. Even the Jangamas were not exempted from doing labour. Thus all members of the state ranging from the Prime Minister to the menial servant, from the priest to the peasant were enjoined to do service. He would often say that the state is the school for citizen; the vocations and professions are educational devices through which the clerk, the teacher, the doctor, the minister are learning while they are labouring in the state. Basava was Prime Minister to a petty king Bijjal who was a usurper. Yet he did not mince matters in convincing this despotic monarch that the solidarity of his kingdom depended upon the strength of the character of his subjects constituting the kingdom. He placed practice before precept, and by his own life rigid rectitude Basava brought home to his countrymen the lesson of self-purification. He raised the moral level of the public life in the country and he insisted that the same rules of conduct apply to the administrators as to the individuals. His administration was based upon love and sincerity; by his moral eminence and practical wisdom he won the hearts of people. He identified himself with the poor, the labourers and untouchables, and made them feel their humanity. The oppression of the poor, the outcast and untouchables which was then a common creed of the despotic monarchy and of the decadent caste system, made the heart of Basava relent and he readily applied himself to their upliftment by removing the social, economic and cultural barriers. He knew that for the safety of any kingdom or state unity must well out from below, from what we call the scum of society, it must not be forced from above, from what we call the cream of society; in other words unity should be rooted in the affections of the entire people.

Basava condemned the caste system chiefly because it did not help to forge unity among the people, because it stood in the way of the solidarity of the Hindus nd prevented the growth of a compact nation. He somhow sensed that caste system is not a division of labour, but it is a division of labourers, a division between the menials and intellectuals. He saw clearly through this evil, and protested against this social inequality which is nt divinely ordained but which is foisted upon society through human selfishness. He made an attempt to break through the cordon of untouchability by bringing about a matrimonial alliance between a Brahmin girl and an untouchable boy. He tried to bridge the gulf between the high caste and low caste by admitting to his Anubhava Mantapa, men and women irrespective of caste, creed, colour, rank or position. The state of Plato was aristocratic since it represented a distinction between the higher and lower classes, whereas the state of Basava might be said to be democratic in the sense that it did not admit division between classes. Basava did not favour a division in which the higher class possesses the esoteric philosophy, while the lower class is fed with mythological fables. He did not advocate philosophy for the few and the fables for the many. He preached not wild, speculative philosophy but a philosophy of life based upon devout love and disinterested action. Thus the cumulative effect of his teaching contributed not a little to the solidarity of state.

The doctrine of inequality as well as equality has been engaging the attention of political thinkers from the days of Plato. In the eighth and ninth books of the Republic, Plato draws a devastating picture of democracy as a condition of society in which everybody does everybody else’s job. Plato was obviously in favour of inequality; to him there was nothing so certain as the natural inequality of men. Those who outlive hardships and sufferings which fall on all alike owe their existence to some superiority, not only of body but also of mind. It will easily be conceived that among such superior minded there would be some who, stimulated by the memory of that which was past, and by the fear of that which might return, would strain to the utmost their ingenuity to control and guide the public affairs. On the other hand, the doctrine of equality engaged the attention of the 18th century thinkers who proclaimed that all men are equal. The Declaration of July 4, 1776 did not originate in the mind of Thomas Jefferson; it had its first utterance in the works of John Locke, and it also reached Jefferson through the minds of several great French men of whom Rousseau and Montesquien were prominent. The object of the American Declaration, as was once said by James Madison, � was to assert, not to discover, truths and to make them the basis of the Revolutionary Act.’ These truths are only too familiar, but none the less worthy of repetition: “We hold these truths to be self evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

This declaration of Independence was the first official document in the world to lay down the basic principles of the democratic way of life. It served as a model for the Declaration of the Rights of Man which was proclaimed by the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century. It established a new order in which there was no place for violation of man’s conscience and his right to freedom. H.S.Commanger, the American historian says that the statement that all men are created equal means that all men are equal in a state of nature, equally entitled to rights. When this principle of natural equality was proclaimed, it then became the duty of Americans to translate it into practice. And this process gradually led to the steady broadening of suffrage, of the abolition of slavery and to many social and economics reforms.

Basava was a mediaeval prophet; to him the problem of equality and inequality as discussed by the political thinkers was not so serious. To him God and the morals were of supreme importance; his saying is, to this effect, that all men are equal in the sight of God, and all men are unequal to each other so far as their moral development is concerned. Basava would agree with Kant when he said that there was nothing in the universe grander than good will. The social instincts guide the lower animals to their end, but in man social instincts are replaced by free voluntary action, guided by social customs and moral laws, enforced by legal, social or divine sanctions. In such a situation, reflective moral judgment, conscience and duty necessarily arise. Gradually the social customs and moral laws are themselves refined by experience, and by the operation of reflective thinking and the insight of gifted leaders. This whole movement from instinct to morality arises, as a part of the whole process of growth which is called creative or emergent evolution. It was in this way that man came to be a free moral agent, and it represented a mighty step upward in evolution when moral conduct took the place of social instincts.

Right actions are those which conduce to social welfare. But what is social welfare? It is, in the concept of Basava, the Highest Good. So long as we are discussing swarms of bees or ants, flocks of birds or herds of animals, there is no difficulty in defining welfare. It is the physical survival of the group or the species. But when we turn to human society, this definition of welfare is no longer adequate. Human beings have higher aims than mere physical survival. It is just here that the disagreement has arisen among the several writers on the theory of State and its end. The good of mankind, order, progress, democracy, liberty, fraternity, utility, the greatest happiness of the greatest number – have all been put forward, at one time or the other, as the ultimate end of the State. Some of them like progress and the good of mankind, when put to the touch-stone of practical application will be found to be vague; others like order, equality, utility and liberty are more in the nature of means, facilitating the achievement of the end rather than to be reckoned as themselves and end. The greatest happiness of the greatest number, the formula propounded by Bentham, is comprehensive enough, but what constitutes the happiness of an individual remains a moot point.

There are three theories relating to the Highest Good and they are the theory of Empiricism, the theory of Intuitionism and the theory of Energism. Empiricism deals with Hedonism, a Greek word meaning pleasure. In its simple form it means that pleasure is the highest good. In its more developed form it puts forward the greatest happiness of the greatest number as the ideal. In modern times, a serious attempt, to construct an ethical philosophy on the basis of happiness, was made by Bentham and Mill. Jeremy Bentham may be mentioned as the exponent of modern utilitarianism. To him pleasure was the highest good, not the pleasure of the moment but of a life-time, and not the pleasure of the individual but of the greatest number. But Mill accepting Bentham’s principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number, makes an important modification in that he recognizes a difference in quality among pleasures. Mill said, “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied.” This very fact of the qualitative difference in pleasures seems to weaken the logical position of hedonism, and it introduces some other standard than pleasure itself. The knowledge of psychology reveals that the desire for happiness is not the primary motive of action. Man is a creature of impulse; by instinct he craves not happiness nor pleasure, but specific things. In the judgment of values man does not appraise pleasure as the highest good. There are other things which are ranked higher – genius ability, heroism, self-sacrifice, devotion to ideals. The great men of the world were not always happy. Jesus was a man of sorrow, Socrates was executed as a criminal, Lincoln fell a victim of a great cause, Gandhiji was murdered. We honour them because they suffered for the happiness of others, because they were martyrs to specific things, to things we count good in themselves. Pleasure or happiness does not seem to be the highest good.

This brings us to the theory of Intuitionism which holds that obedience to duty is the highest good. Kant’s whole moral system was an emphasis upon duty. The practical reason expresses itself in the form of a categorical imperative which is called the voice of duty. The will is self-legislative issuing its orders categorically, hence unconditional obedience to the moral law is the sole motive of moral action. Kant tried to explain the intuitive character of the moral sense by the postulate of the autonomy of the will. But the empiricist would try to explain it away as the result of individual or racial experience in living under a system of moral discipline. Empiricism and intuitionism are not at logger heads to each other they are complementary because if empiricism recognizes the importance of experience in the growth of our moral ideas, intuitionism recognizes the element of intuition involved in all reflective thinking.

The theory of Energism holds that the highest good is found in the normal activity of our highest powers. In modern times Energism usually takes the form of self-realization, in which the principle of activity is still the essential one. The end in view is to be a person, to develop all that is inherent in personality, and to exercise all the powers and enjoy all the privileges of a person. But the fate of the individual is bound up with the fate of the society. When one speaks of loyalty to the society as the highest good, this is because it is something which is absolutely fundamental. So vital are our duties to society that the word character values they therefore well stand at the head of any list of values, conditioning all the others.

Basava attempted to formulate the highest good in accordance with the principle of self-realization, bringing the individual and society into their proper relations. The end of all moral action is “a social order in which each member of the group may have a fair field for his activities and the fullest opportunity for self-realization without infringing upon the similar right of every other member of the group. “The highest good is” a social order in which the highest potentialities of each indivudal are developed to the maximum, and in which these potentialities are expended in the interests of that order to guarantee its stability and permanence.” In this scheme the organic unity of society, the supremacy of the character values and the principle of self-realization of the individuals in society are recognized. Basava put forward his scheme and tried to work it out in his administration, but unfortunately he could not reap the harvest as he was compelled to leave the capital and take refuge in Kudala Sangama, at the unsavoury turn of events which took place after the marriage of the Brahmin girl with the untouchable boy.

The idea of the welfare state was first enunciated and practiced by Ashoka. He ruled over a vast empire in a benign spirit. He tells us himself in his edict, “All men are my children, and just as I desire for my children that they may obtain every kind of welfare and happiness both in this and next world, so I desire for all men….. The welfare of the whole world is an esteemed duty with me, and the root of it is exertion and dispatch of business. I can therefore never be satisfied too much with my exertion, or dispatch of my business in the matter of administration… I cause this document of Dharma to be engraved in order that it may endure for a long time and that my sons and grand-sons may similarly exert themselves for the welfare of whole world.” The virtues which Ashoka mentioned as constituting Dhamma, are goodness, cleanliness, mercy, liberality, truth and gentleness; and the duties which he regards as binding upon everybody are non-violence, obedience to parents, attendance on elders and reverence to teachers. It is clear that character values head the list and they from the highest good of the welfare state.

The values which have been preached to us in the past from every pulpit and platform are liberty, equality, opportunity, efficiency and organization. We still believe in them fully, but the time has come when our attention must be focused upon the other values which condition the existence and welfare of society, such as self-restraint, respect for law, obedience to duty, temperance and co-operation. The practice of these virtues has become urgent and imperative. It seems probable that in the years to come we shall have to put more emphasis upon the character values. The reason for this is that the world is now knit into a family, and it becomes more and more difficult to live in hatred or enmity. The only way that people and nations can live together in harmony is by the practices of the character values. The world is now full of degenerative forces not known in former times. But a new social conscience is arising, and there are visions of new values in the relation between individuals and society. That a crisis has arisen in the moral progress of the world no one can doubt, but that catastrophe is imminent is by no means sure. Above the rivalry of nations and the clash of classes, above the hatred, suspicion and fear which grew out of the war, there is a power of divine thought which is slowly but surely discerning a better way to live. There are many honest men and women who have the clearer vision, and there have been a few great leaders who could see that the path of progress lies through righteousness and cooperation. Dharma teaches that the universe is friendly, that the law of cooperation is deeper and wider than the law of competition, that altruism is as primordial as egoism. It teaches that in our struggle for right; the universe in its spiritual depths, is on our side, so that the struggle is not in vain.

Taking these words to heart, let us strive hard to build a better society and a beneficent state.

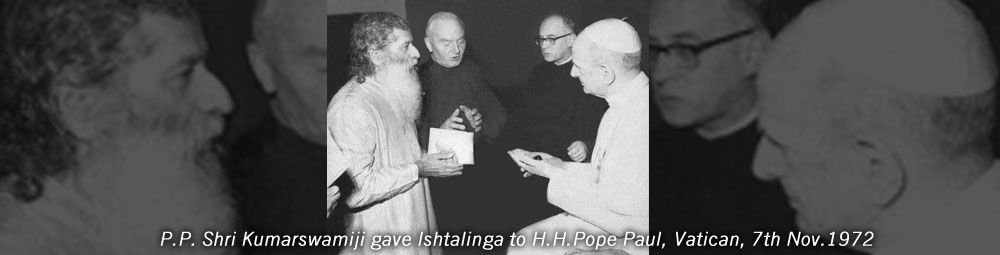

This article – Basava and the Welfare State – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Buddha and Basava’.