After Buddha it was Chennabasava, the young Veershaiva saint of the 12th century who started the movement of rationalization in religious life. Chennabasava appeared on the religious firmament by the middle of the 12th century on Karnataka. He and his colleagues known as Sharanas or the Veershaiva mystics or saints initiated the doctrine of golden mean in all the walks of life. It is obvious that this doctrine of the mean is the formation of a characteristic attitude which appears in the sayings of almost every saint. Basava had it in his mind when he called virtue, enlightened faith; Chennabasava when he named virtue harmonious action; Allama Prabhu when he identified virtue with self-knowledge.

Man’s aspirations are numerous, yet four aspirations have been singled out as prominent by Indian philosophers and they are the Dharma or righteousness, Arhta or wealth, Kama or pleasure and Moksha or deliverance. Dharma takes the precedence of the other three aspirations of man, why’ because by justice or rightful means alone do wealth, pleasure and liberation become the lawful ambitions of man. For wealth secured without righteousness or in excess results in a chaos of social life; pleasure in a chaos of individual life and liberation in a chaos of spiritual life. Dharma always aims at the cosmos that is, at the order and beauty of life, this can be had only when excess is avoided in all walks of life. Excess has to be avoided by all means, this is the central message of the Mahabharata. The echo of this message is heard in far off Greece, because the seven wise men had established the tradition by engraving on the temple of Apollo at Delphi, the motto meden agan ‘ nothing in excess.

Dharma is justice in the Platonian sense. Justice, says Plato, is the having and doing what is one’s own. What does the definition mean’ It means that just man is a man in just the right place, doing his best, and giving the full equivalent of what he receives. A society of just men would be therefore a highly harmonious and efficient group; for every element would be in its place, fulfilling its appropriate function like the pieces in a perfect orchestra. Justice in a society would be like that harmony of relationships whereby the planets are held together in their orderly movement. Where men are out of their natural places the coordination of parts id destroyed, the joints decay, the society disintegrates and dissolves. Justice is effective coordination. In the individual too justice is effective coordination; the harmonious functioning of the elements in a man, each in its fit place and each making its cooperative contribution to behaviour. Every individual is a cosmos or a chaos of desires, emotions and ideas; let these fall into harmony and the individual survives and succeeds. Let them lose their proper place and function, let emotion try to become the light of action as well as heat, or let thought try to become the heat of action as well as its light, disintegration of personality begins, failure advances like the inevitable night. Justice is a taxis kai that is, Kosmos ‘ an order and beauty of the parts of the soul. All evil is disharmony between man and nature, between man and man, between man and himself. Dharma in one sense is moderation and it is from moderation that harmonious strength springs. Plato also said the same thing, ‘justice is not mere strength but it is harmonious strength, it is harmonious strength, it is not the right of the stronger but the effective harmony of the whole. If the individual who gets out of the place to which his nature and talents adapt him, may for a time seize some profit and advantage, but an inescapable nemesis pursues him so much so that the terrible baton of the nature of things drives the refractory instrument back to its place and its pitch and its natural note.’ There is nothing new in this concept, nothing which plumes itself on novelty; it simply states the moral law of nature. Morality begins with association, interdependence and organization. Life in society requires the concession of some part of the individual’s sovereignty to the common order, and ultimately the norm of the conduct becomes the welfare of the group. Nature will have it so and her judgment is always final. A group survives, in competition or conflict, with another group, according to its unity and power, according to the ability of its members to cooperate for common ends. And what better cooperation could there be than that each should be doing that which he can do best’ This is the goal of organization which every society must seek if it would have life.

The concept of Dharma, as adumbrated by Mahabharata, is justice in the Platonian sense or moderation which seeks the middle path between the two extremes. Dharma always inclines towards the golden mean. The golden mean however is not like the mathematical mean, an exact average of two precisely calculable extremes. It fluctuates with the collateral circumstances of each situation, and discovers itself to mature and flexible reason. Virtue is an art won by training and habituation, in other words, virtues are formed in man by his doing the actions. We are what we repeatedly do, not all actions but only those actions that are good and conducive to social and individual welfare. If all evil is disharmony, good is harmony. Action therefore presupposes knowledge. One should act with knowledge and understanding. Virtue depends upon a clear judgment, self-control, symmetry of desire and artistry means. It is not the possession of the simple man, nor the gift of innocent, but the achievement of experience in the fully developed man. Yet there is a road to it, a guide to excellence which may save many detours and delays; it is the middle way, the golden mean. According to Aristotle, the qualities of character may be arranged in triads, in each of which the first and last qualities will be extremes and vices, and the middle quality a virtue or an excellence. So between cowardice and rashness is courage; between stringiness and extravagance is liberality; between sloth and greed is ambition; between humility and pride is modesty; between secrecy and loquacity is honesty; between moroseness and buffoonery is good humor; between quarrelsomeness and flattery is friendship; between Hamlet’s indecisiveness and Quixote’s impulsiveness is self control. Right then in ethics or conduct is not different from right in mathematics; it means correct or what works best to the best result. But youth is the age of extremes. If the young commit a mistake it is always on the side of excess and exaggeration. The great difficulty of youth is to get out of one extreme without falling into its opposite. For one extreme easily passes into the other whether through over-correction or elsewise; insincerity does protest too much and humility hovers on the precipice of conceit. Those who are consciously at one extreme will give the name of virtue not to the mean but to the opposite extreme. Sometimes this is well; for if we are conscious of erring in one extreme, we should aim at other end so we may reach the middle position.

Mahabharata is the first book which proclaims the Golden Mean; the golden mean, as it were, presupposes the life of reason; it is not everybody, but only a man of reason who can find the mean or centre of a circle. Anybody can get angry, that is an easy matter, but it is difficult to bring under control the passion of anger. Anybody can give or spend money, but to give it to the right person, to give the right amount of it, and give it at the right time, for the right cause and in the right way, this is no an easy matter. The discovery of golden mean means avoiding the evil of excess and the evil of deficiency. That is the reason why it is always difficult and yet noble to do well. The Sanskrit word ‘Sukruta’ means well done. The meaning of art also is that which is well done. If this is so then whatever is well done is a fine art and the conventional distinction between the economic, the ethical and aesthetic activities should disappear. There is only one art, the art of doing well. Sometimes it is called virtue or excellence which includes the useful, the good and the beautiful. The art of doing well is a creative activity which releases the hidden energy for higher purposes. Our life is largely a round of merely passive processes. We wake, we walk, we work, we sleep ‘ all these are passive processes. The passivity of our ordinary life must be transformed into the activity of the good life. This is what the golden mean teaches us, this is what the life of reason is. Vyasa was the great figure who, as is shown in his Mahabharata seems to have been pioneer to forge and build the missing link of thought power, the might power of Reason. The exemplar of the manner is the Gita. Gita says, ‘the golden mean lies between action and inaction, between Rajas and Tamas. Between Rajas and Tamas is Sattva which is equilibrium which denotes balanced activity.’ Vyasa started a movement of rationalization in his own way in India which was taken up later by Buddha and his followers. It was Buddha’s credit to have brought into play the power of the rational intellect and used it in support of spiritual experience. It seems to be true that in Buddha and his authentic followers the movement came to the forefront of human consciousness and attained the proportions of a major member of man’s psychological constitution. In Kalama Sutta Buddha says: ‘Do not believe in what you have heard; do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations; do not believe in anything because it is rumoured and spoken by many; do not believe in that as truth to which you have become attached by habit; do not believe merely on the authority of your teachers and elders-after observation and analysis when it agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit to one and all, then accept it and live up to it.‘ And Buddha struck a golden mean between the ascetic life on the one hand, and material life on the other.

After Buddha it was Chennabasava, the young Veershaiva saint of the 12th century who started the movement of rationalization in religious life. Chennabasava appeared on the religious firmament by the middle of the 12th century on Karnataka. He and his colleagues known as Sharanas or the Veershaiva mystics or saints initiated the doctrine of golden mean in all the walks of life. It is obvious that this doctrine of the mean is the formation of a characteristic attitude which appears in the sayings of almost every saint. Basava had it in his mind when he called virtue, enlightened faith; Chennabasava when he named virtue harmonious action; Allama Prabhu when he identified virtue with self-knowledge. All these were attempts of Sharanas which reflected the feeling that passions are not of themselves vices, but the raw material of both vice and virtue, according as they function in excess and disproportion or in measure and harmony. There is a pertinent saying of Chennabasava, ‘Desire, anger, avarice, attachment, pride and envy are the raw material of life. These are needed and not-needed. Desire is not needed in another’s women, but desire is needed towards the love of God. Anger is not needed in the elders and the preceptors but righteous indignation is needed for the correction of behaviour. Avarice is not needed in the worldly possessions but it is needed for the company of good; attachment is not needed to the another’s woman, wealth and wine; attachment is needed to the virtue and gaining of excellence. Pride is not needed in one’s possession but it is needed in this that the soul is possessed of the Divine. Envy is not needed in the created beings, for sympathy is the hall-mark of humanity; but envy is needed in the sinful acts.’ If matter out of place is dirt, mind out of balance is disease. The instincts and emotions that go to constitute the structure of mind should be properly placed. The displacement of these is disease, the proper placement of these is good or virtue. Instincts and emotions are never absolute but only relative. A certain instinct or emotion in human nature is deemed to be less abundant than it ought to be; therefore we place a value upon it and cultivate it. As a result of this valuation we call it a virtue but if the same quality should become super abundant we should call it a vice and try to repress it. The instincts and emotions are the raw material of life, they should be sublimated and transformed into the fine texture. This is what the life of reason demands.

We the modern people love the sound of the word big. We pride ourselves upon the fact that we belong to the biggest country in the world, and possess the biggest navy and grow the biggest oranges and potatoes and love to live in the biggest cities and when we are dead we are buried in the biggest burial place. A saint of the 12th century, could he have heard us talk, would not have known what we meant. Moderation in all things as the ideal of his life and mere bulk did not impress him at all. And this love of moderation was not merely a hollow phrase used upon special occasions; it influenced the life of the Sarana from the day of his birth to the hour of his death. It was part of his life and literature and it found expression in his dress and demeanour. ‘Of what avail is it to add and add and add” Asks poet Tagore. ‘by going on increasing the volume or pitch of sound we can get nothing but a shriek. We can get music only by restraining the sound and giving it the melody of the rhythm of perfection.’ The life of reason therefore imposes upon man self restrain which is the heart of Golden mean.

There are three systems of ethics, three concepts of the ideal character and the moral life. One is that of Buddha and Jesus which stresses the compassionate virtue, considers man ad an end unto himself, resists evil only by returning good, identifies virtue with love and inclines in politics to democracy. Another is the ethic of Machiavelli and Neitzsche which stresses the heroic virtues, accepts the inequality of men, relishes the risks of the combat and conquest, identifies virtue with power and exalts an hereditary aristocracy. A third, the ethic of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, denies the universal application of either the feminine or masculine virtues, considers that only the informed and mature minds can judge according to diverse circumstances; when love should rule and when power identifies virtue with knowledge, and advocates a varying mixture of aristocracy and democracy in government. This is the distinction of Chennabasava that his ethic reconciles these apparently hostile systems, weaves them into a harmonious unity and gives us in consequence a system of morals which is the supreme achievement of medieval thought.

Chennabasava finds a rapprochement between reason and will, between perception and action. If reason lies in the perception of law in the chaotic flux of things, Will lies in the establishment of law in the chaotic flux of desires. The golden mean lies in making perception and action fit for the eternal perspective of the whole. Thoughts help us to this larger view because it is aided by imagination and imagination becomes creative when it is freed from the moorings of passive memory. By imagination and reason we turn experience into foresight; we become the creators of our future and cease to be the slaves of our passions. So we achieve the only freedom possible to man. The passivity of passion is human bondage, the action of reason is human liberty. Freedom is not from causal law but from partial passion or impulse. We are free only when we know; therefore freedom comes always with self-knowledge. To be a Superman or a Sharana is to be free not from the restraints of social justice and amenity but from the individualism of the instincts. With this completeness and integrity comes the equanimity of the wise man; not the aristocratic self-complacency of Aristotle’ hero, much less the supercilious superiority of Nietzsche’s ideal, but a more stable poise and peace of mind. To be great is not be placed above humanity bossing over others, but to stand above the partialities and futilities of unformed desires and to rule one’s self.

This is indeed a nobler freedom than that which men call free will. Let no one suppose that he is no longer the structure of his life. Man thinks himself free because he is conscious of his volitions and desires and ignorant of the causes by which he is led to wish and desire. Every instinct is a desire developed by nature to preserve the individual or rather the species. Pleasure and pain are the satisfaction or the hindrance of an instinct, they are not the causes of our desires but they are results. We do not desire things because they give us pleasure, but they give us pleasure because we desire them. The necessities of survival determine instinct, instinct determines desire and desire determines thought and action. In ethics Chennavasava inclines towards determinism. In one sense all education presupposes determinism and pours into the open mind of youth a store of prohibitions which are expected to participate in determining conduct. Determinism makes for a better moral life, it teaches us not to despise or ridicule any one, and though we punish miscreants it will be without hate; we forgive them because they know not what they do. Determinism teaches us to bear and forbear, to remember that all things follow by the eternal decrees of God. Perhaps it will even teach us the intellectual love of God whereby we shall accept the laws of nature gladly and find our fulfillment within her limitations. So grounded in calm knowledge he rises from the fretful pleasures of passion to the high serenity of contemplation which sees all things as parts of an eternal order and development. He learns to smile in the face of the inevitable and whether he comes into his own now or in a thousand years he sits calm and collected. He learns that God is no capricious personality absorbed in the private affairs of his devotees, but the invariable sustaining order of the universe. So the philosophy of Golden Mean teaches us to say yea to life and even to death’ It calms our fretted egos with its large perspective; it reconciles is to the limitations within which our purposes must be circumscribed. It may lead to resignation but it is also the indispensable basis of all wisdom and of all strength.

The principles of the Golden Mean are simple, clear and intelligent. First of all the Golden demands that we should have enlightened faith in the intelligent Being which is the source and origin of all things. God is the immanent and not the extraneous cause of all things. All is in God, all lives and moves in God. If this is so the universal law of nature and the eternal decrees of God are one and the same thing. God is the causal chain, the underlying condition of all thing, the law and structure of the world. This concrete universe of modes and things is to God as a bridge is to its structure. The world is upheld by the will of God. The will of God and the laws of nature being one and the same reality diversely phrased, it follows that all events are the operation of invariable laws, and not the whim and caprice of an irresponsible autocrat seated in the stars. The world is not a design but a determinism in the sense that the Will of God determines the process of the world. AS the will expresses itself in the laws of nature, the laws of nature can be mastered not by defiance but by obedience. This obedient, this reverent attitude towards God and nature is what constitutes enlightened faith.

The second basic principle of Golden mean is non-violence. Violence in any shape or form cannot lead to any kind of lasting peace and socio-economic reconstruction. True democracy and real growth of human personality are possible only in a non-violent society. Violence breeds greater violence and whatever is gained by force needs to be persevered by force. Prof. Laski has frankly recognized the futility of active hatred and violence and advocates a revolution by consent: ‘For hate is of all qualities the most cancer-like to its possessor. It leads us to develop in ourselves the character we condemn in others. The spiritual life of Europe belongs not to Ceaser and Napoleon but to Christ; the civilization of the East has been more influenced by Buddha than by Chengiskhan and Akbar. It is that truth we have to learn, if we are to survive. We therefore believe that solutions made by democratic consent prove, in the end, to be more lasting than those imposed by the coercion of violence.’ In a planned society planning is only a means and not an end in itself. Even if it were the end, it is not that the end always justifies the means. In order to preserve the purity of the end, the means employed towards its attainment must be equally pure. That is why Golden Mean maintains that even a socialist society should be established through non-violence and not through a bloody revolution.

The Third basic principle of Golden Mean is the dignity and sanctity of manual labour. To Chennabasava labour is the law of nature and its violation is the cause of economic poverty and physical unfitness. The Greek’s disdain for manual labour is well-known. Manual labour, Aristotle believes, dulls and deteriorates the mind, leaves neither time nor energy for political intelligence; it seems to Aristotle a reasonable corollary that only persons of some leisure should have a voice in Government. Leisure is good and necessary up to a point only. But the lure of leisure was carried to an absurd length by the Greek’s, so much so that they were always doing something to keep themselves for doing nothing. And in the words of Shaw, the best definition of Hell is perpetual holiday.

Chennabasava not only underlined the necessity and desirability of physical labour only on moral and psychological grounds, but he was anxious to strike at the root of economic exploitation by insisting on every one becoming as self-sufficient as possible. But if we have almost self-sufficient village communities in which every one works for his or her living on a co-operative basis, there will be almost no room for exploitation.

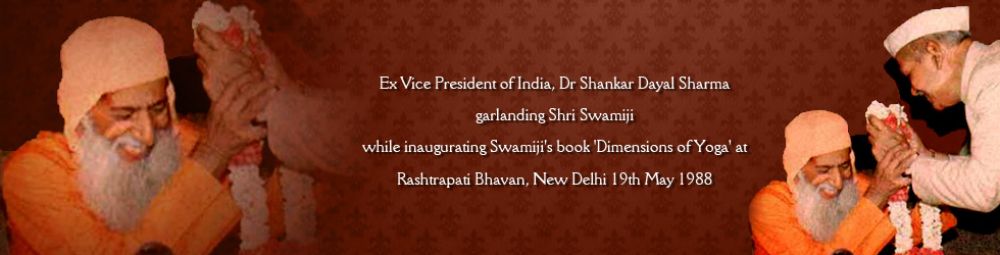

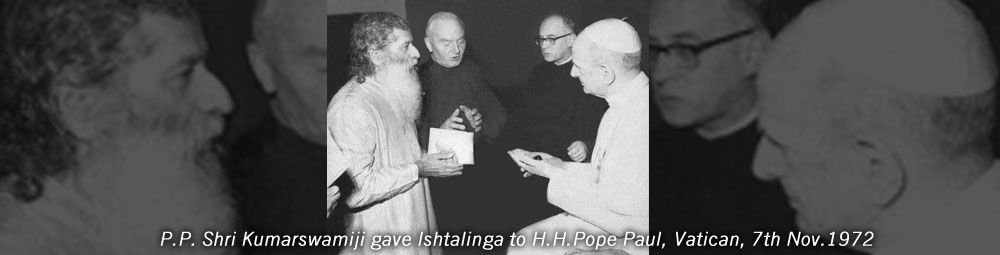

This article – ‘Chenna Basava’s – Yoga of Golden Mean’ – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Dimensions of Yoga’.