There is a readiness now to admit the possible existence of a human faculty, hitherto unrecognized by science, by means of which communications may take place between mind and mind, through channels other than those of the senses. It is by virtue of this faculty that the soul holds communion with the Supreme, puts itself in tune with the Infinite, so much so that the abnormal experiences, the supra-mental powers reveal themselves that attest the existence of a supra-physical and extra-mundane plane. One of the rarest of all acquirements is, therefore, the faculty of profitable contemplation. For contemplation is the nurse of thought, the tongue of the soul and the language of our spirit. No soul can preserve the bloom and delicacy of its existence without silent prayer and lonely musings; it is the harmonious voice of creation, an echo of the invisible world. “Contemplation is the life of the soul, action is the soul of contemplation; so contemplate that thou mayst act, so act that thou mayst contemplate upon the glory of God.” This is the religion of the Sharana or mystic. This is the mysticism of a true religionist or Sharana.

The Sharana accomplishes good character, that is, a perfectly educated will by conquering the unruly desires of the Ego through virtuous action. Likewise he achieves a coordinated knowledge or comprehensive wisdom by unifying the pure aspirations of the Super-ego or the Soul through vivid contemplation. To the Sharana the soul, being of divine origin, is God’s glorious image, it is synthesis that shines as a spark of fire. The Sharana is fully convinced that the soul is indestructible and that its activity will continue through eternity. To look upon the soul as going on from strength to strength, to consider that it is to shine forever with new accessions of glory and brighten to all eternity is agreeable to that innate disposition which is natural to the mind of man. Everything here, but the soul of man, is passing shadow. The only enduring substance is within the soul. When man awakes to the sublime greatness and the glorious destiny of the immortal soul, he is nearest to the Supreme. For the wealth of a soul is measured by how much it can feel the presence of the Supreme, its poverty by how little. Contemplation is therefore the soul’s perspective glass, whereby in its long removes, it discerns God, as if he were nearer at hand. “By contemplation I can converse with God,” says the Sharana, “solace myself on the bosom of the Divine life, bathe myself in the rivers of divine pleasure, tread the path of my rest and view the mansions of eternity.” Since the Supreme is the ground and goal of the synthesis, it is the divinity of soul that stirs within man, it is the idea of immortality that points out a hereafter and intimates eternity to him. The intellect of man sits visible enthroned upon his forehead, but the soul reveals itself in the Anahata-nada only, as God revealed Himself to the prophets of old ‘in the still small voice and in the voice from the burning bush’. There is in souls a sympathy which sounds, and as the wind is pitched, the ear is pleased with melting airs; some cord in unison without we hear, is touched within us and the soul replies. Because of this still small voice within, the soul is able to fly heaven-ward and perceive the glories of God. So remarks Michael Angelo: “Heaven born, the soul a heaven-ward course must hold; beyond the world she soars; the wise man, affirm, can find no rest in that which perishes, nor will he lend his heart to aught that doth on time depend.”

The more the soul hears the still small voice of God within, the more it becomes detached from the remora of desire, the shackles of egoism and the limitation of the sense mind, the higher it soars into the luminous sky of consciousness. All vision depends upon this detachment of the soul or rather the organization of the dissociated mental states, whether functioning when asleep, when subconscious or when contemplative. Our daily life of the waking state brings to all of us sad and anxious hours and to most men it brings days of monotonous labour. But to everyone, whatever the sorrow or the toil of the day may be, night should bring release. When we enter into sleep we are not only liberated from the bondage of labour, but shackles are loosened which by day keep the imagination tied to earth. Only in sleep the imagination is set at liberty and is free to exercise its full powers. Sleep which brings us our dreams fulfills the eternal need within us – the need of romance, the need of adventure; for sleep is the gate which lets us slip through into the enchanted country that lies beyond, since there is detachment of the soul to some extent. Leigh Hunt observes: “It is a delicious moment, certainly, that of being well nestled in bed and feeling that you shall drop gently to sleep. ….. A gentle failure of the perceptions creeps over you; the spirit of consciousness disengages itself once more, and with slow and hushing degrees, like a mother detaching her hand from that of a sleeping child, the mind seems to have a balmy lid closing over it, like the eye – it is closed, the mysterious spirit has gone to take its airy rounds.” We are thus somewhat more than ourselves in our sleep and the slumber of the body seems to be but the working of the soul. It is the litigation of sense, but the liberty of spirit; and our waking conceptions do not match the fancies of our sleep. The fancies of our sleep are but the fabrications of the dream mind. Given such a dissociation or detachment the dream mind, with the help of a creative imagination, would fabricate the illusion of any objective event. For the mind is capable of creating almost any kind of hallucination, even to the extent of shaking hands with an imaginary spirit, provided it is not contradicted by the conflicting awareness of reality. We have therefore in dreams no true perception of time – a strange property of mind. The relations of space and time are also annihilated, so that while almost an eternity is compressed into a moment, immense space is traversed more swiftly than by real thought. It would be easy to cite examples of the day-dreamer or trance-dreamer in whose fantasies distance is annihilated and centuries pressed over in the twinkling of an eye. As in normal dreams, the soul may seem to leave the body and hover in space or be transported to another sphere, celestial or cosmic.

Scientific men are still absorbed in the triumphs of that wonderful age of discovery in the physical world. They have hardly begun to find out how great is the work awaiting science in the field of Psychology. Many of them still regard psychology with a certain suspicion and have not recognized that any purpose, useful to science can be served by the study of semi-conscious, or super-conscious state of the mind. But M.Bergsom wars the scientists by saying, “That the principal task of psychology in this century will be to explore the secret depths of unconscious, and that in this, scientific discoveries will be made rivaling in importance, the discoveries made in the preceding century, in the physical and natural science.” It is not until recent years that investigation of certain secrets of man’s personality, by means of the revelation of the mind in sleep and trance, have begun to attract the attention of men of science. The initial attempts at explanation of the psychology of dream or trance is purely a material or physiological one. Dreams arise from disturbances communicated to the brain by the system of nerves, acting much as a telegraph wire acts, which inform the brain of the existence of local trouble or distress in some part of the body. Such perturbations of the brain, when they occur during sleep occasion our dreams. But medical thought has moved very far from this stand-point. Some of the greatest physicians are devoting themselves to special branches of medical psychology. They have come to realize the immense, the almost incalculable power of the human mind over the body, and are therefore ready to study every manifestation of the mind and its subtle processes.

“They that are whole have no need of the physician, but they that are sick.” The metal processes of those that are whole, the dream imagery of those of us who are fortunate enough to enjoy the sound bodily and mental health need not be subjected to the doctor’s scrutiny, but the cases that generally come under the doctor’s notice are the cases of nervous or morbid people; or of persons who, owing to temporary conditions of illness are not for the moment normal or healthy. The conclusions, that a specialist particularly interested in this study draws, are influenced by the proportion of more or less morbid subjects that he will come across. This is an inevitable drawback from which Freud suffers, a specialist of medical psychology. His dream theory, briefly stated, is that dreams are symbols of desires, thoughts or fears, that are sternly repressed by day and that are not admitted to our waking consciousness. By day they are therefore unable to intrude their presence upon us, but by night, when our will-power is in abeyance, they dart upon us appearing themselves allegorically and always under a disguise in dreams. Dr. Freud has so elaborated his theory of the dream as the symbol of repressed desire, and of the distortion of the unconscious wish in the dream construction, that one is compelled to see the sex impulse alone amongst other impulses as the force which is able to affect the dream-mind. Many of our dreams are indeed symbolic or allegorical in from but they represent in different ways the moods and thoughts which have occupied our minds by day. Mr. Arnold Forster proposes an explanation of dream-construction which is as ingenious as it is simple. The mechanism is that of association of ideas with the co-operation of the imagination. In dream building, one idea calls up another by successive association, that is free association, unhampered by critical and discriminating judgment. The dream imagination that seizes upon certain elements in the associated ideas, intensifies and objectifies them in imagery by which objects are vividly visualized. Thus, “In a dream, a winding path in a landscape suggests by association a rail road, which is at once visualized and also in the landscape. The two crossing each other suggest a rail-road crossing, which is in turn visualized; then follows the idea of danger from a possible approaching train, and Presto!. The sound of such an onrushing train is heard; and so on, one association calling up another to be vividly represented in images and worked by imagination into a connected story, the images suggesting thoughts and vice versa. The whole is very much like the process of certain types of thinking carried on when awake by day.”

A more curious and much rarer type of dream than any of those have hitherto been described is what may be termed the super-dream. In this type of dream, the dream-mind, working beyond its ordinary level of capacity, has actually solved problems that have defeated the efforts of the normal mind in its working hours. Henri Fabre explains that sleep in his case was often a state which did not suspend the mind’s activity but actually quickened it, and in sleep he was able at times to solve mathematical problems with which he had struggled by day. “A brilliant bacon flares up in my brain, and then I jump from my bed, light my lamp and write down the solution, the memory of which would otherwise be lost; like flashes of lightning, these gleams vanish as suddenly as they appear.” Very similar to his experience are the dream-creations which are so fully described by R. L. Stevenson in his essay called ‘A Chapter on Dreams’. He describes the process of inventive dreaming from which many of his stories originated. So completely do these dreams seem to him to be an inspiration from outside himself, the operation of faculties apart from the workings of his normal mind and working at a higher level, that he speaks of them as being the handiwork of the “Little people”, Brownies of the mind, who bestir themselves to construct or elaborate for him the plots of his stories, far better tales, he declares, than any that he can invent for himself by day. These and many equally curious and interesting experiences seem to require the assumption of a secondary consciousness existing side by side with our ordinary personal consciousness. Unless we can assume the presence of such a divided personality or consciousness, it seems almost impossible to conceive how certain processes of the mind are carried out in the dream-state or in the hypnotic state. Dr. Morton Prince opines that “Certainly there are dreams, as might be illustrated from my own collection in which there is an argument, the end is foreseen and the whole is a well worked-out story or allegory. No associative process alone could have produced such logical coherence. In such dreams the motivating dispositions which have determined the theme and inspired the creative imagination are another matter and are to be searched for in the antecedent conscious life of the individual.”

What is this antecedent conscious life of the individual but the super-ego? The super-dream is the handiwork of the super-ego which displays the supra-mental faculties. The methods of the super-mind, the qualities of its imagination, its habit of seizing upon part of an argument or part of a story to weave into something new and strange – all these are quite unlike the ways of the normal mind that is familiar to any by day. The difference in their methods of working is so sharply defined that one should seldom have to question which is the author of the particular train of thought. They work differently and arrive at different results; and herein lies undoubtedly a great part of the unexpectedness and charm of the super-mind. We find in it something of the attraction that is to be found in mystics, in the inspiration of poets and thinkers, in the spiritual vision of saints and sages, whose outlook is not quite like our own and who bring to it qualities of mind that delight us and display the presence of the Supreme Being. The Greek sensed the super-mind as the matrix of the archetypal ideas which find their fulfillment in the artistic sense of beauty. To him art ‘is the most powerful momentum in human life’, that is, something within the soul of man which, when once started, goes on with undiminishing vigour through eternity. Art then may be thought of as the only form of expression which tells us something of the ‘infinite passion, and the pain, of hearts that yearn’. The mystics in their search for their different stages and degrees of intuition of Eternal life explore the resources of all the arts – poetry, music, dancing – to raise themselves to the pitch of what Coventry Patmore once spoke of as a ‘sphere of rapture and dalliance’. Many typical examples of these degrees may be cited to confirm it. Shri Basava and Akka Mahadevi had the celestial visions of their beloved deities of Sangamnatha and Chenna Mallikarjuna; Allam Prabhu had heard the Anahata-nadanusandhana; the ‘unstruck music of the Infinite’; Siddharmeshwar would scale the heights of Kailas that is to say, of the cerebrum and see there the saints dancing in the sphere of Sahasrara; and many a sharana had many a vision and voice in accordance with their capacity to respond to the vibrations of the super-mind.

F. Myers writes : “There is reason to suppose that our normal consciousness represents no more than a slice of our whole being. We all know that there exist subconscious and unconscious operations of many kinds – both organic, as secretion, circulation, etc., that are in a sense below the operations to which our minds attend; and also our mental, as the recall of names, the development of ideas, etc. that are on much the same level as the operations to which our minds attend, but which for various reasons remain in the background of our mental prospects. Well, besides these sub-conscious and unconscious operations, I believe that these super-conscious operations are also going on within us – operations, that is to say, which transcend the limitation of ordinary faculties of cognition, and which yet remain not below the threshold, but rather above the upper horizon of consciousness, and illumine our normal experience only in the transient and cloudy gleams.” Between these two borders of Ego and Super-ego, of mind and super-mind, widely varying stages of consciousness are included within this border-land state. It embraces experiences far removed from dreams, apparently unrelated to our dream-life and which have a very special character of their own. The initial yet important characteristics of border-land state which has been experienced by every sensitive mystic of any age or any clime is the curious heightening of sense-impressions that take place when sleep is approaching. For example, three or four tiny grains from a spike of lavender will at such moments an effect of a concentrated lavender essence, and a scent so delicate that it would pass almost unperceived by day acquires at these times a powerful fragrance. The Sharana or the mystic becomes, in fact, like the princess in the fairy tale who, when she lay down to sleep, was able to detect the presence of a pea, hidden beneath the seven mattresses on which she rested. So is it with the other sense impressions. It is gratifying to learn that Shri Basava, the Messiah of the Lingayat Faith, has been represented by his colleagues and contemporaries as a man possessing Pancha-purusa, meaning thereby he had attained the heightened sensitiveness of the faculties of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch.

Besides this heightened sensitiveness, in the earlier state of tranquility, certain mental faculties appear to operate with heightened powers. At such moments the answer to some difficult question, which has intrigued us and baffled our intelligence by day, may flash into the mind, appearing to come to us from without rather than from within. The missing links of thoughts that were needed have been supplied, we know not how; we are only aware that whereas something was previously lacking, the chain of thought is now entire, and the deduction drawn from it is complete. In this condition, transformation, so to say, takes place; for, we find that the mind is working in a manner different from that which is normally characteristic of it. Any faculty of the mind changes its character and assumes functions different from those which it possesses normally. If the mystic is to do his work of transformation, he needs to have an open mind to science, to philosophy, to religion, to all the life’s problems as they are transmuted by the various great department of life. For all these are related. The more there is of religion – that is to say, the way, that the individual transforms the changing universe – the more fully the message of science, the higher and nobler will be his conception of religion. The mystic, then, if he is to do his work rightly, must be a rounded man in his inner nature. He must be sensitive, not only with his sensorium, but also with the intuition, the mind and the emotions. Especially must he be sensitive to all kinds of ideas. Hence one may say that each mystic must profess all the faiths and philosophies and yet none. For his message is not to the universe in the abstract; it is distinctly to mankind, to us, to find ourselves. We are the source of power in the universe, but we have to find ourselves, and the mystic art enables us to find. In India the voice is heard from the beginning of time that the only religion which a man should profess is ‘So-aham – I am God’. But it is the proclamation of all genuine mystic art, for the individual finds himself again as that permanent, unchangeable spiritual entity, as he bodies forth mysticism.

Thomas Traherne, ‘the divine philosopher’, has composed the Centuries of Meditations which is considered his magnum opus. Dr. Tallock, in his Rational Theology has succinctly summarized the under-current of these ‘meditations’ in the following words: “No spiritually thoughtful mind can read them unmoved. They carry us so directly into an atmosphere of divine philosophy, luminous with the richest lights of meditative genius. ….. We see a mind religious to the core ….. His mind is fresh as a new-born life, with open eyes of poetic wonder and divine speculation. He has not painfully reached the serene heights on which his thoughts dwell; but these heights are the natural level of his lofty and abounding spiritual nature.” If one would like to closely study and parallelize it with a number of the sayings of the Sharnas, he would doubtless find a very close resemblance subsisting between the Centuries of Meditations and the sayings of the Sharanas. Traherne’s magnum opus is entirely based on the mature study of the Bible. It is no less a manual of contemplation. Each century depicts the progressive stages of contemplative life. Likewise we are apt to discern a psychological sequence in the contemplative life of the Sharana. The state of contemplation is peculiar not only by reason of the heightened sensitiveness of organs and the mental faculties but also because it is the condition in which the soul puts itself in tune with the Supreme. The mystery and elusiveness of the mental phenomena which belong especially to the contemplative state have always made a strong appeal to thinkers like F. Myers and those who have followed along similar paths of enquiry. They are bold enough to acknowledge that many of these phenomena lie beyond man’s present knowledge and still elude his understanding. There is a readiness now to admit the possible existence of a human faculty, hitherto unrecognized by science, by means of which communications may take place between mind and mind, through channels other than those of the senses. It is by virtue of this faculty that the soul holds communion with the Supreme, puts itself in tune with the Infinite, so much so that the abnormal experiences, the supra-mental powers reveal themselves that attest the existence of a supra-physical and extra-mundane plane. One of the rarest of all acquirements is, therefore, the faculty of profitable contemplation. For contemplation is the nurse of thought, the tongue of the soul and the language of our spirit. No soul can preserve the bloom and delicacy of its existence without silent prayer and lonely musings; it is the harmonious voice of creation, an echo of the invisible world. “Contemplation is the life of the soul, action is the soul of contemplation; so contemplate that thou mayst act, so act that thou mayst contemplate upon the glory of God.” This is the religion of the Sharana or mystic.

This is the mysticism of a true religionist or Sharana.

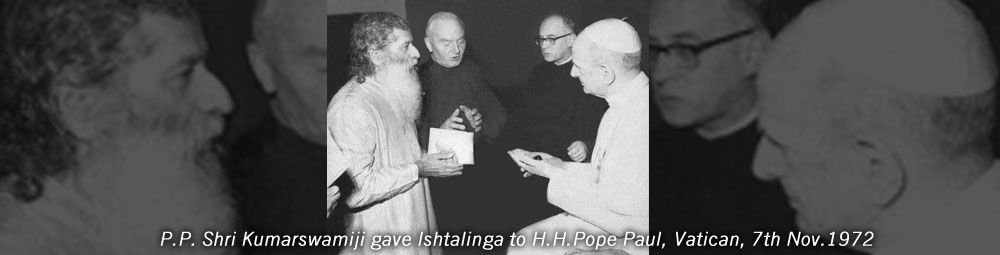

This article – Mysticism of Sharanas III – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Virashaiva Philosophy and Mysticism’.