Aristotle observed that the seat of the soul was in the heart and he arrived at this conclusion by noticing that the diseases of the heart are the most rapidly and certainly fatal, that that psychical afflictions, such as fear, sorrow and joy cause an immediate disturbance of the heart and that the heart is the part which is the first to be formed in the embryo. Add to these the psychological experiments of Professor Callegaris who has discovered three communicating disks in the human body and one of which he has posited in the hand. It will be seen then, that the head, the heart and the hand of the body shall be considered by the western thinkers as the most direct points with which the soul comes into contact, thus corresponding with Shira-sthala, Ura-sthala and Kara-sthala of Virashaivism.

Virashaivism offers us the most complete synthesis of the spirito-psychological discipline. As philosophy, it presents a synthesis of thoughts, as spiritual discipline, it presents a harmonization of spiritual cultures. Its out-look is therefore synthetical, its basic discipline is harmony. Ancient psychology accepted the soul and was chiefly concerned to distinguish the various functions of the soul, so as to assign them seats in the various parts of the body. In this, it only anticipated however dimly, the truth of the modern experimental psychology which observes that there are some telepathic points in our body. Professor Callegaris, a famous Italian specialist of experimental psychology says that thought-waves will be the means of enabling persons, thousands of miles apart, to communicate with one another. He believes that there are three ‘communicating disks’ in the human body and one of which he places behind the index finger of the right hand. This statement confidently proves that there is a ‘Law of Correspondence’ between body and soul; and between body and soul linking them together is mind with which modern psychology is chiefly concerned. In all we have a trinity body, mind and soul which the Sharana or the Lingayat Mystic calls them respectively by the names of Tanu, Mana and Dhana or Bhava. And each one of the trinity has a triple aspect; soul is Sat-Chit-Anandatmaka, that is, it is at once a Divine Presence, Power and Peace; mind is Kriya-Jnana-Icchatmaka, that is, mental activity is a cyclic process of cognition, conation and affection; body is Shira-Ura-Karatmatka, that is, corresponding to these triple of activity of mind and soul there are three points in bodily organism namely the head, the heart and the hand.

Cogitating upon the fact that the ‘Law of Correspondence’ holds good with respect to body, mind and soul, the first question with which rational psychology begins is the question of the seat of the soul in the body. Hence it is germane to rational psychology to concern itself with a discussion of the part or parts of the body, with which the soul comes more directly into contact. Professor James says, “In some manner our consciousness is present to everything with which it is in relation. I am cognitively present to Orion whenever I perceive that constellation but I am not dynamically present there; I work no effects. To my brain, however, I am dynamically present in as much as my thoughts and feelings seem to react upon the processes thereof. If then by the seat of the soul is meant nothing more than the locality with which it stands in immediate dynamic relations, we are certain to be right in saying that its seat is somewhere in the cortex of the brain.” Descartes imagined that the seat of the soul was the pineal gland, while Lotze maintained that the soul must be located somewhere in the “structure-less matrix of the anatomical brain elements, at which point all nerve currents may cross and combine.” Aristotle observed that the seat of the soul was in the heart and he arrived at this conclusion by noticing that the diseases of the heart are the most rapidly and certainly fatal, that that psychical afflictions, such as fear, sorrow and joy cause an immediate disturbance of the heart and that the heart is the part which is the first to be formed in the embryo. Add to these the psychological experiments of Professor Callegaris who has discovered three communicating disks in the human body and one of which he has posited in the hand. It will be seen then, that the head, the heart and the hand of the body shall be considered by the western thinkers as the most direct points with which the soul comes into contact, thus corresponding with Shira-sthala, Ura-sthala and Kara-sthala of Virashaivism.

The culture of the head, the culture of the heart, the culture of the hand! These three types of culture have been cribbed, cabined and caged respectively in the Upanishads, in the Bhagavata and in the Agamas, the hoary scriptures of Hinduism. The quest of the Upanishads is truth, the final and fundamental truth; but this quest is more through intellect than through life. The main effort of the Vedanta is therefore not the psychological opening but fine understanding which enables us to transcend the limitations of the formal mind. Hence the Vedanta rejects any other approach than the intellectual, which in the end rears up fine intellectual intuition, culminating in the consciousness of pure God-head, one without a second, ‘Yekmeva Advitiyam Brahma’, as the sole reality. In the undifferentiated Godhead of the Upanishads we see the mind’s attempt to conceive that Reality as unchanging yet changer of all, as the unconditioned Absolute in which all is resolved, as the only substance that survives. “In philosophy, substance is that which underlies or is the permanent subject or cause of all phenomena, whether material or spiritual; the subject which we imagine to underlie the attributes or qualities by which alone we are conscious of existence, that which exists independently and unchangeably in contra-distinction to accident, which denotes any of the changes of changeable phenomena in substance, whether these phenomena are necessary or causal, in which latter case they are called accidents in a narrower sense. Substance is with respect to the mind, a merely logical distinction from its attributes. We can never imagine it, but we are compelled to assume it. We cannot conceive substance short of its attributes, because those attributes are the sole staple of our conceptions; but we must assume that substance is something different from its attributes.” We cannot conceive substance but we are compelled to assume it; yes, conception is psychological, assumption is logical. Since Vedanta rejects any other approach than the logical, it naturally leads to the cultivation of the cognitive faculties culminating in the cusp and apex of intellectual intuitionalism, which is really the culture of the head.

The Bhagavata School represents a definite tendency of thought with an emphasis more upon concrete spirituality than upon the transcendent wisdom of the Upanishads. The specialty of the Bhagavata lies then in laying stressing upon the concreteness of the Divine. But this concreteness reaches its fullness in the conception of Bhagavan, where the devotional spirituality reveals its full nature and finds its free play. The Divine is essentially concrete; because of its concreteness it exhibits its essence as a supra-person embracing as well as transcending finite souls. For amongst the souls themselves there is a dynamic identification or an internal relation or to be precise a prehension in the words of Whitehead. A prehension is a grasping or taking hold of one thing by another, but this grasping includes an element of activity, an active taking into relation instead of a passive being in relation, which be still finer the rich harvest of the life in Love cannot be reaped. This life in Love has illumined Ananda. The Bhagavata lays more emphasis upon the bliss aspect of the Divine since it has the greatest attraction for the finite souls. But this bliss is not to be identified with the crude feeling of pleasure but it can well be associated with all finely expressive activity that is Beauty. What is beauty? Beauty is essentially expression and the expression which is conscious must of necessarily be rhythmical and harmonious. Beauty is the divine on the point of expression; and the soul of beauty lies in bliss. Bliss consists in serene, tranquil and unlimited expression and ineffable delight. This delight is expressed in radiant feeling and transparent joyousness through the refined emotions of the heart.

The spirit in its self-expression, according to the Bhagavata is love, beauty and bliss. It is love, for it is ever attractive to the soul; it is beauty, for it is finely rhythmical in its expression; it is bliss, for delight is its being. He has divorced power from spirit in its inward being, for majesty and power are to him conceptions relative to cosmic regulation, not to the inner self-expression of spirit to itself. Power may not exhibit the finest in the Divine but power is necessary for cosmic adjustment. Love alone can never attract the earth towards heaven and integrate humanity and divinity in indissoluble union. The spiritual kingdom on earth can only be established when the forces are responsive to the finest urges of the Divine life; when the Time-Spirit is ripe, the Divine in its beauty and love, with all its wealth of power can intervene in the cosmic regulation. The truth is that at the back of cycle of civilization works unseen the power which controls and destroys the dark forces and the Love that cements humanity into a divine federation on earth. It is this power, Shakti, the transcendent Will that forms the theme of the Agamas.

The Agamas lay stress upon the dynamic principle, Shakti, which is integrally associated with Shiva, the Static, Shakti is immanent in Shiva, it is the force of projection in creation and the force of withdrawal in liberation. It is the creative energy of all possibilities – spiritual, psychic, vital, cosmic as well as individual. Hence it is the transcendent will which is not only a principle of active force and knowledge and creation of the worlds, but also is an intermediary Power and state of being between that self-possession of the one and its hidden multitudes; it creates the many but does not lose itself in their differentiations. It possesses the power of development, of evolution, of making explicit; and that power carries with it the other power of involution, of envelopment, of making implicit. “This Divine Nature or Shakti has therefore a double power, a spontaneous self-formulation and self-arrangement which wells naturally out of the essence of the thing manifested and expresses its original truth, and a self-force of light inherent in the thing itself and the source of its spontaneous and inevitable self-arrangement.”

In the Vedanta this Shakti has been thrust into the background but in the Agamas it has been kept in the foreground. Herein lies the great difference between the Vedanata and the Agamanta; for the former lays stress on transcendent spirituality, while the latter emphasizes dynamic spirituality. But we must note this important divergence of opinion and observe that the two opposing views carry with them important consequences, practical as well as theoretical. On the first view, which lays stress on the absolute transcendence of God, there will be a disposition to despair of the world and human progress, and to seek the Kingdom of God wholly in the unseen; on the second view, which lays emphasis on the divine immanence, there will follow naturally a religion which has affinities with humanism and seeks the Kingdom of God partly through the promotion of human progress. Hence it is argued by those who take this view that creativeness is an essential characteristics of the Divine Nature; that creation is not an illusion but an act of will.

– OM SHANTI | OM SHANTI | OM SHANTIHI –

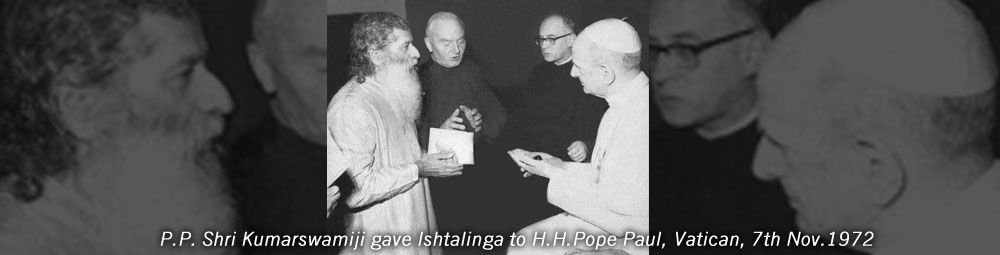

This article ‘Nisus in Virashaivism’ is taken from H.H.Mahatapsvi Shri Kumarswamiji’s book, ‘Virashaiva Philosophy & Mysticism’.