The vachana-shastra is to the Lingayata community what the stars are to the astronomers. But if the community spends all its time in gazing upon it, marveling at its splendour and uniqueness rather than observing the lofty principles it enunciates and proclaims, the real value and worth to the community will be lost. On the whole the truths of the vachana-shastra have the power of awakening an intense moral feeling in the human beings. They send a pulse of fellow-feeling through all domestic, civil and social relations and teach men how to love the righteous things and deplore the wrongs. They seek each other’s welfare in the right sense of self-sacrifices but not in the shadow of enlightened self-interest. They control the baneful and bastard passions of the heart and thus make men proficient in self-government. Finally they teach man to aspire after God and fill him with the hopes of purifying, exalted and conformable to his nature so as to secure an intuition of the Supreme Being.

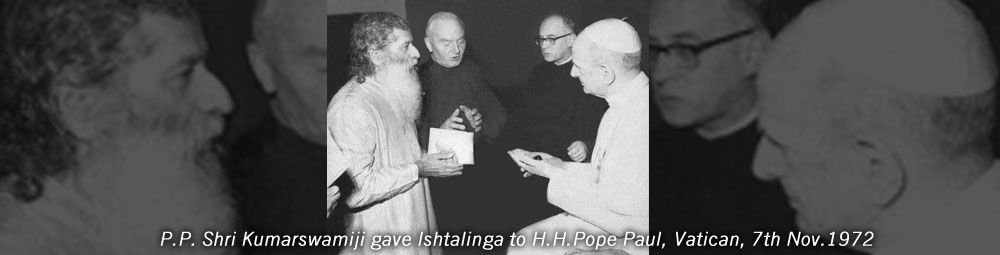

Veerashaivism in a sense can be considered as being inspired by the basic philosophy of Shaivism, though it is distinctly different from Shaivism and has come into being as a great religion on its own. The word Veera prefixed to Shaiva is intended to distinguish between the two aspects of Shaivism. The characteristics feature of Shaivism is the worship of Shivalinga in the temples. Shivalinga is a visible representation of the self-existent truth. But the distinctive hall-mark of Veerashaivism is the worship of the Ishtalinga. Veerashaivism advocates the wearing of Linga on the person by practicing Veerashaivas so that the body becomes a temple fit for the God to dwell in. The Linga thus worn becomes the symbolic presence of God not in the far-off Heavens but in the very cells of the human body. The wearing of the Linga reminds the wearer of the constant existence of the Divine Presence in him/her. In fact, it brings home the belief that the individual wearing the Linga is in constant contact with Shiva. At the present time, there are over twenty million faithful Veerashaivas spread over India, though a great majority of them reside in Karnataka. It is heartening to mention here that there are two overseas Veerashaiva organizations, namely the Veerashaiva Samaja of North America and the Veerashaiva Samaja of United Kingdom.

The term Lingavanta is comparatively of a later date, yet it vividly expresses the fact that the followers of Veerashaivism wear the Linga and the significance of the wearing of the Linga on their bodies. The term Veerashaiva, however, does not distinctly bring out the idea of Linga worn on body as the word Lingavant does. But over the centuries, the two words have become synonymous and are used interchangeably. Lingavanta is the nominative plural of Lingavat. The possessive Sanskrit affix ‘Vat’ as in the words ‘Bhagavat’ and ‘Dhanavat’ conveys both characteristics of ‘Dhana’ and possessor. Similarly, Lingavan expresses the characteristics of Linga and its possessor. Lingavan is the nominative singular of Lingavat and denotes a single individual wearing the Linga. But Lingavanta is the nominative plural and the use of the plural with reference to a single individual bespeaks of courtesy and respect. A Lingavanta is, therefore, the possessor of a Linga, or one who always wears Linga, the symbol of God, the symbol of infinity upon his/her body.

A Veerashaiva is often addressed as Lingavanta or Lingayat. What does Lingayat mean? ‘Ayata’ means ‘that which has come’. In Veerashaivism, there is a convention that the Guru or the preceptor bestows Linga upon the child after it is born. Again the Guru confers Linga upon a disciple at the time of initiation. In any case, the Linga must come from the Guru and he who wears Linga that has come from the Guru is called Lingayata. If the term indicates the necessity of initiation of Diksha, the term Lingavanta expresses the need for wearing the Linga on the body. The 12th century Karnataka witnessed renaissance in Veerashaiva religion and literature. The leading figures of the renaissance were Basava and Allama Prabhu. Many a sharana flocked under Basava’s banner. Almost all the Veerashaiva saints of that epoch have expressed their spiritual experiences in the form of sayings (Vachanas) on various topics in various strains. The collection of these sayings is known as Vachana-shastra.

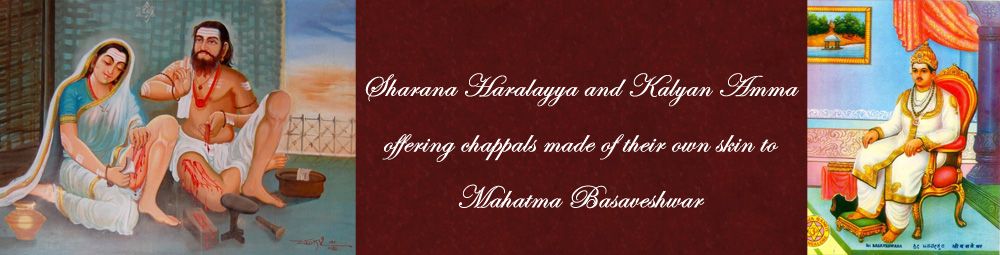

The Sharanas or the Vachanakaras (the writers of the vachanas) were free thinkers. Though they had the respect for the authority, they did not hesitate to differ from the Agamas whenever the situation warranted it. In some Agamas, it appears as though some importance is attached to the castes. In the seventh chapter of the Shukshma-agama, it is stated that there are seven divisions among the Veerashaivas, which are based on the order of castes. In the third chapter of the same Agamas it is stated that Shadakashara-mantra should not be imparted to women and shudras. But in the vachanas we find definite departure from the Agamas on this score. Vachana writers have unanimously stated that all persons irrespective of caste, colour, creed, gender and social status become equal the moment the get initiated. No distinctions of any kind do they countenance among the Lingayats. Another important difference is found between the vachana-writers and the Agama-writers is the matter of emphasis laid on one’s duty in a spirit of worship. The vachana-writers have eloquently sung in praise of the relationship between work and worship. In fact they equated work (Kayaka) to heaven (Kailas, Shiva’s abode). This unusual importance attached to work is not found the Agamas, which are merely content by making reference to it.

The Veerashaiva religion as professed and practiced in Karnatak during the past several centuries forms a significant chapter in the history of Indian culture and finds its full significance in the Vachana-shastra. No doubt it has absorbed several elements from Trika, the Shaiva Siddhanta and other Indian schools, but the assimilation of all these elements into the entity that is known as Veerashaivism is itself an achievement of no mean distinction. The Ashtavarns, the Shatasthalas, the wearing and the worship of the Ishtalinga, the various Veerashaiva rites etc lend credence to its claim as a distinct, independent religion. Its puritan fervour is duly marked, so is its essential democratic spirit. Caste and sex differentiation are obliterated and social and religious rights are afforded equally to all members. Mysticism is brought within the purview of every day religion, realization is interpreted as a process and the union with Shiva, is to be achieved here and now and in this life. Religion is explained as a being and becoming and religious life is not to be divorced from the commitments to the family and society. Manual labour and services of man are also considered as aspects of religious life. In fact the secular life and the spiritual endeavour are harmonized into the pilgrim’s progress towards realization. �Democratic in spirit, puritanical in fervour, with service as its watch-word and Shata-sthala for its sign post, Veerashaivism blends together man’s spiritual and social ideas and teachers the art of righteous living.’ Since all these elements are faithfully reflected in the vachanas, the scholars are delighted to admit the vachana-shastra as the basic scripture (literature) of the Veerashaiva religion.

The credit of having brought religion to bear upon every day life of man goes to Basava. He lived the practical side of religion and thereby set an eternal example to the masses. To him, we owe the superb social structure of Veerashaivism raised on the foundation of practical philosophy of Kayaka or work. All this is revealed to us in the vachanas of Basava and other saints. The entire vachana-shastra is the glorious moment of Basava’s supreme personality. The vachana-shastra preaches a socio-religious conduct of life as obtained from practical experience of life. ‘All that we find therein is human endeavour for social and spiritual freedom that resulted in the divine achievement only because it was sincere and unselfish. The vachana literature of the Veerashaiva saints who came together under the banner of the new movment unfurled by Basava was followed suit and the result was the growth of similar vachana literature of the post Basava period.’ The vachanas are said to be like the Upanishadas in poetic fervour and profoundity of meaning. They are very telling, soul-stirring and unfailing in their effect. The vachana literature is voluminous now coming gradually to light and immensely appreciated. Whoever turns over the pages of the Vachana-shastra cannot but feel that it is original. There is freshness and vigour about it which is unique and innovative to literary composition. This uniqueness characterized it as an outstanding contribution not only to the Kannada literature but also to the world literature.

The vachana-shastra is the fruit of deep meditation and careful observation of nature by the Veerashaiva saints. It contains true sublimity, exquisite beauty, puritanical morality and fine strains of poetry. In whatever light we may regard the vachana-shastra, it is a veritable gold mine of knowledge and virtue. The more deeply one works the mine, the higher and more abundant one finds the ore. More light continuously beams from this Scripture to direct the conduct and illustrate the work of God and ways of men. As all Scriptures of the world, it teaches us the best way of living, the noblest way of suffering and the most comfortable way of dying. The importance and values of the vachana-shastra can not be too greatly emphasized in these days of uncertainties, when men and nations are prone to decide a question, from the stand-point of expediency rather than in the light of eternal principles. Scholars may quote high authorities in their studies, but the hearts of the thousands will recite their vachanas at their daily toil and worship and draw strength from their inspiration as the meadows draw it from the brook. A wide-spread interest and admiration is displayed in the vachana-shastra now a days by the Lingayat community but a mere interest or admiration without an insistent application of the truth to life is as good as a pig in a flower garden. The vachana-shastra is to the Lingayata community what the stars are to the astronomers. But if the community spends all its time in gazing upon it, marveling at its splendour and uniqueness rather than observing the lofty principles it enunciates and proclaims, the real value and worth to the community will be lost. On the whole the truths of the vachana-shastra have the power of awakening an intense moral feeling in the human beings. They send a pulse of fellow-feeling through all domestic, civil and social relations and teach men how to love the righteous things and deplore the wrongs. They seek each other’s welfare in the right sense of self-sacrifices but not in the shadow of enlightened self-interest. They control the baneful and bastard passions of the heart and thus make men proficient in self-government. Finally they teach man to aspire after God and fill him with the hopes of purifying, exalted and conformable to his nature so as to secure an intuition of the Supreme Being.

– OM SHANTI | OM SHANTI | OM SHANTIHI –

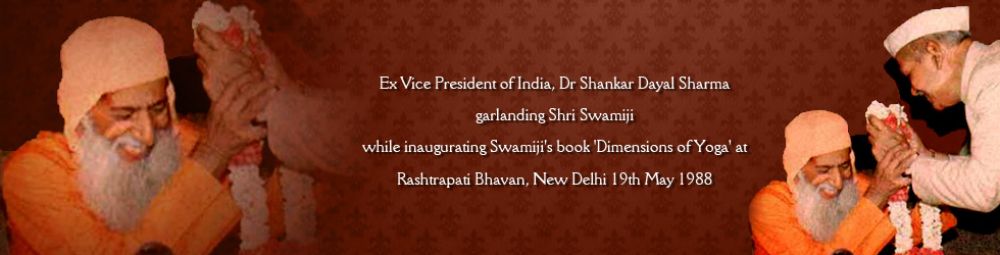

This article ‘The Vachana Shastra’ is taken from H.H.Shri Kumarswamiji’s book, ‘Veerashaivism : Comparative Study of Allamprabhu,Basava,Shunya-Sampadane And Vachana-Shastra’.