The Vachana-shastra exhibits the unity of the three-fold nature of the wisdom known as Siddhanta, Sadhana and Sampadana. Siddhant or Tattva is the philosophic apprehension of Linga; Sadhana or hita is the moral and spiritual method of knowing it; sampadana or purushartha is the realization of God or Linga which is the summum bonum of life. This innovative religion upholds the dignity of labour, practices monotheism – the worship of only one God in the form of Ishtalinga and it denounces the caste system of the Vedas and Smritis. Many a saints have sung the vachanas, which are noted for their charm, simplicity, elegance of diction and depth of the sublime thought. The unparalleled reforms of the Lingayata religion initiated and introduced by Basava have transformed Veerashaivism into one of the most modern organized religion.

The sayings of the Sharanas or the Veerashaiva saints are characterized by a variety which exhibits the richness of the wisdom and the wealth of knowledge in an incomparable manner. In the first place there is a variety of enigmatic saying which occur in the vachans of almost all the saints and more than half of the vachanas of Prabhu are enigmatic; the spirit of detachment and idealism is obviously manifested throughout his vachanas whose cryptic expression expresses in a way that Carlyle in his Sartor Resortes, Shakespeare in his Sonnets and Tennyson in his In Memorium.

The crystallization of the philosophical truths in aphorisms and riddles is a specialty of the brilliant Indian thinkers from a remote time. The same tradition Allama Prabhu presents in his sayings and in the Shunya-Sampadane. His, vachanas abound in riddles and aphorisms. This style has a built-in disadvantage as well as an advantage. His style is precise and direct. He does not mince words. He expresses his opinion forthrightly and freely. There is an indescribable beauty and charm in such an expression, as Nietzsche and Aurelus have shown. The disadvantage is that it teases the intellect, for it has to struggle and battle to comprehend and to achieve a synthesis of what is presented. But intensity of the expression which is compressed in the aphorisms or riddles compensates for the disadvantage, for it radiates light multi-dimensionally and centrifugally. A fair acquaintance with philosophy and mythology of Hindu religion, at its highest, will make the task easy, for the theory of correspondence rests on the theory of symbolic substitutions through similes and metaphors.

“A merchant of Jambu Isle

Gathering his bales and bundles;

Sets up his stall

In the womb of Mother Earth

Stricken with a crazy thirst

He drank up the seven oceans

Until to his own dismay

At the unquenchable thirst

He sucked the ooze itself

An infant carries his mother�s corpse

Upon his back and goes

Mumbling her name

Behold a globe-like icon

Has swallowed the glory of Guheshwara!

On Heaven’s expanse

A strange parrot was born;

And she built her a house

In vain glorious pomp.

But of that one parrot

There are born five and twenty

Brahma was the parrot’s cage

Vishnu his victuals;

And Rudra his perch

Whe she swallowed her young ones

In front of those three

Behold! Oh! Guheshwara

The phenomenal play cease to have its sway.”

In Upanishads and Plato�s works we rarely come across the riddles or enigmatic sayings. In the Sveta-svetatar Upanishad it is said that nature, is like a vast expanse of water, contributes by the five different streams of the senses, whose springs are the five elements which make it fierce and crooked, whose waves are the five Pranas, whose fount is the Anthakarana Pnachaka, whose whirl-pools are the five objects of sense which entangle a man into them, whose five rapids are the kinds of grief caused by generation, existence, transformations, decay and death, which diverts itself into the fifty tides of periodic overflow namely at birth, in childhood, in manhood, in old age and death. As saying of Plato amounts to a riddle when he describes how a man and woman, seeing and not seeing, a bird and no-bird, a tree and no-tree, killed it and did not kill it, with a stone and no-stone.

Secondly, there is a variety of aphoristic sayings, which are pregnant with thought, though terse in style. “Is there any room for lust in a lover of God?” “How can I call him an immaculate whose body is subject to disease and decay”. The vachanas of the sharanas are teaming with brief but brilliant utterances. Thirdly, there is a variety of etymological sayings. Channabasava has given the etymological meaning of Linga: In the term Linga, there are three words – ‘Li’, ‘zero'( or dot ) and ‘Ga’. ‘Li’ represents the Infinite while ‘Ga’ stands for the finite and it is a ‘zero’ that unites the finite and the Infinite. He who knows this secret is a real mystic.” Fourthly, there is a variety of dialectic sayings which are resorted to very often in the vachana literature for the purpose of inculcating moral excellence. Basava advises a Sadachari thus: “Steal not, kill not, speak no untruth, be not angry, show not contempt for others, do not pride upon thy virtue, do not speak ill of others – this is the way to internal purity, this is the way to external purity, this is the way to win God�s favor”. Fifthly, there is a variety of analogical sayings characterized by similes and metaphors. It is a belief of the mystic that God dwells in the heart of men, in the soul of his being. The relation of God and soul, or the Divine and the Devotee is often expressed by simple yet sublime similes. The Pinda-sthala of the vachana literature abounds in the analogical sayings. A saying of Basava runs thus:

“As submarine fire is hid in the waters of the sea,

As a ray of ambrosia is hid in the moon

As fragrance is hid in the maiden

So God is hid in the heart of the Sharana

Oh! Lord of the Spiritual Unification – Kudala Sangamdeva.”

Sixthly, there is a variety of dialogic sayings. The entire Shunya-Sampadane is an illustration of the dialogic method which involves the symposium of the various sharanas. Seventhly, there is a variety of satirical sayings. Satire is a form of literary composition in which vice or folly of a person or a community deemed as guilty, is held up to ridicule. The sharanas have condemned the outmoded religious practices, archaic and unworthy disciplines in a strong language. They did not hesitate to hold up to ridicule a person or community guilty of any vice, folly and profligacy. Lastly, there is a really existing thing which stands for and images forth a greater reality of which it is itself an instance. Symbolism often involves allegory which is the interpretation of experience by means of images. The Vachana literature is prolific of the symbolical sayings which are characterized by vivid imagery and vital truth. The saying of Shanukhaswami bears testimony to this fact: “Behold the same thing! The husband – preceptor touches the wife-disciple. The contact release the six-lettered mantra, which is deposited in the matrix of the ear of the wife-disicple. Then the mind becomes impregnated and son-linga is born of the uterus-eyes. The son-linga is placed on the palm symbolizing cradle and a lullaby of the suspicious hymn is sung naming him Akhandeshvara. Oh! Lord thou art therefore, my child and I am thy mother.”

The Vachana shastra exhibits the unity of the three-fold nature of the wisdom known as Siddhanta, Sadhana and Sampadana. Siddhant or Tattva is the philosophic apprehension of Linga; Sadhana or hita is the moral and spiritual method of knowing it; sampadana or purushartha is the realization of God or Linga which is the summum bonum of life. Tattva is a consideration of the reality under the aspects provided by the three regions of the philosophic knowledge, namely epistemology, ethics and aesthetics, considered under these aspects, God is the Sat without a second, that wills the many and the will differentiates into the manifold of sentient and non-sentient beings. The Sat is the all-inclusive unity or the Absolute that imparts substantially to all beings and thus sustains all existence and value. Though God is the cause for all changes, He by Himself does not change. However, change is the essence of the universe. Every atom in the universe is in constant motion. All things without exception, even the so-called fixed stars move perpetually and nothing stays put in one place. The very earth which we inhabit is speeding through space with a velocity of about nineteen miles per second. One Being in the universe, however, is without change and that Being is God. Though absolutely immutable, the Being is the cause of all motion, the same yesterday, today and forever. It is this reason that Ling or Being is defined as the real of the reals. It is likewise termed greater than the greatest for it is the abode of all eternal values. Linga is again defined as the light of lights, for it illumines the suns and the stars and is the inner light of the individual self.

The idea that God is the cause of all things does not imply that creation is an act having a beginning in time. The universe of the living and the non-living is an eternal cyclic process with pralayas, dissolution and sristi, creation alternating with each other. In pralaya the world remains latent as a real possibility and srsti is the actualization of what is possible. The entire creative process is the self-expression of God. Hence the logical idea of the cause cannot be sundered from the ethical concept of the purpose. The process of nature and the progress of man can be explained only as the self-actualization of the divine will. The philosophic intellect strives to reduce the entire experience to a single unity but it fails to satisfy the demands of the moral consciousness. The Sat, without a second may be the logical greatest but it is indifferent to the deeper ethical values of human life. The definition of God has therefore to be restated in the language of moral philosophy involving such terms as the ruler and the redeemer, when restated the definition of God takes the form of Shakti-vishistha-advaita, for Shakti or divine will implies purpose and the purpose of the cosmic process is to provide an opportunity for the individual soul to realize its divine destiny. To the logical intellect refers to the transcendental eminence and holiness of God. God is the righteous ruler of the world, dispensing justice according to the deserts of each soul. The goodness of God as the ruler and redeemer functions through the moral freedom of man and hence is no contradiction between the infinite power of God and the moral freedom of man.

This moral freedom of man presupposes the law of Karma. Karma is the application of the law of cause and effect to moral experience. The recognition of Karma is indirectly the recognition of the cosmic law and order. The cosmic order is just and properly maintained. Cosmic justice demands that there should be the strict and equitable retribution in nature. Thus no action can escape the good or evil consequences of man�s deeds accruing to him. Psychologically, Karma implies that every action must have its effect in the form of Samskaras or the engram complexes, good or bad according to the law of retributive justice. But in its ethical aspect the law of Karma affirms the freedom of the soul, for freedom is a real possibility and the soul can train its instinctive urges, subdue them and sublimate them. On the religious level the law of Karma is not all powerful, for the grace of God transforms the righteous law and it becomes the ruling principle of religion. The contradiction between Karma and Krpa is negated simply because redistribution and redemption do not coexist. Karma then becomes an attitude of surrender to the Divine Will. The fruit of man�s actions belong not to God and himself or rather it belongs to God in him. Then his will becomes a true Will: “it does its share, it leaves its quota, it returns to its Master with its talent used or increased.” The surrender of the human will to the divine will, will redeem the soul from sin and suffering. Redemption is the central motive of the divine grace. Moksha or liberation consists in the attainment of freedom from the shackles of Samasara by seeking the redemptive love of God.

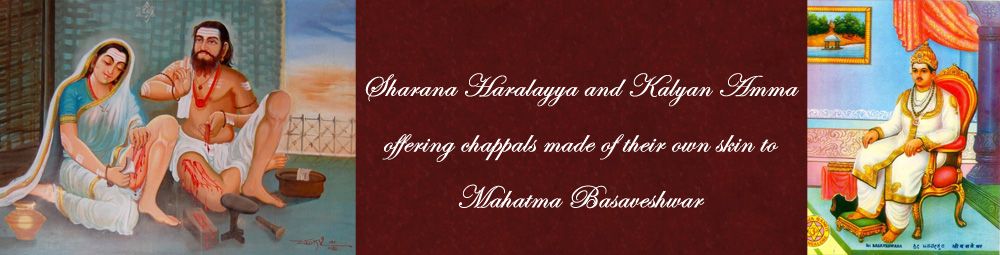

Veerashaivism as a social force owes its birth to Basava. It gathered momentum from Shivanubhava Mantapa, the religious house of experience. Shivanubhava Mantapa was a spiritual and social institution. Basava founded this institution around 1160 AD primarily to make a man aware of his/her place in the scheme of the universe; to breathe a fresh air and to usher in a new spirit into the then decaying religion; to give women equal status and an independent outlook; to abolish caste distinctions; to glorify manual labour by equating it with the worship of God, to countenance simple living and singleness of purpose. This institution bears eloquent testimony to the genius of Basava, whose field of action was as varied as it was vast. It reveals not only his practical wisdom but also the happy blending in him of hand, head and heart.

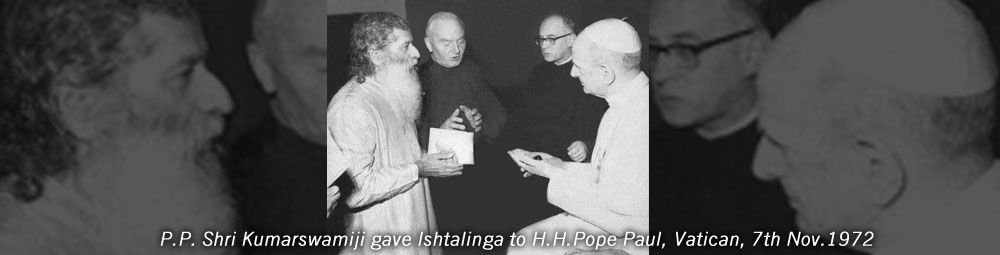

The members of the Lingayata or Veerashaiva community are adherents to ahimsa and hence are vegetarians. They vehemently condemn cruelty to animals and animal sacrifices. According to Basava, Daya (kindness) is the hall-mark of the religion. The position held by woman among the Lingayata community is highly unique. They have as many rights and privileges in the religious, social and educational spheres as the males. They are entitled to Diksha Samaskara and are eligible to read the scriptures. Female education was insisted upon so that the Veerashaiva woman was accepted as national heroine, poetess and mystic. Examples are: Mahadevi, Muktayi, Nagambika, Nilambika, Gangambika, etc. These Sharaneyaru and their contemporaries are regarded and respected women-saints. They rendered invaluable services to the propagation and popularization of the Lingayata religion. This innovative religion upholds the dignity of labour, practices monotheism – the worship of only one God in the form of Ishtalinga and it denounces the caste system of the Vedas and Smritis. Many a saints have sung the vachanas, which are noted for their charm, simplicity, elegance of diction and depth of the sublime thought. The unparalleled reforms of the Lingayata religion initiated and introduced by Basava have transformed Veerashaivism into one of the most modern organized religion.

– OM SHANTI | OM SHANTI | OM SHANTIHI –

This article is taken from H.H.Shri Kumarswamiji’s book, ‘Veerashaivism : Comparative Study of Allamprabhu,Basava,Shunya-Sampadane And Vachana-Shastra’.